About this handbook #

What the program is about1 #

Effective altruism (EA) is an ongoing project to find the best ways to do good, and put them into practice.

Our core goal with this program is to introduce you to some of the principles and thinking tools behind effective altruism. We hope that these tools can help you as you think through how you can best help the world.

We also want to share some of the arguments for working on specific problems, like global health or biosecurity. People involved in effective altruism tend to agree that, partly due to uncertainty about which cause is best, we should split our resources between problems. But they don’t agree on what that split should be. People in the effective altruism community actively discuss and disagree about which causes to prioritize and how , even though we’ve learned a lot over the last decade. We hope that you will take these ideas seriously and think for yourself about which ways to help are most effective.

Finally, we give you some time at the end of the program to begin to reflect on how you personally can help to solve these problems. We don’t expect you’ll have an answer by the end of the eight weeks, but we hope you’re better prepared to explore this further.

What the program involves #

Each part of the program has a set of core posts and sometimes an exercise.

We think that the core posts take most people about 1-2 hours to get through, and the exercise another 30-60 minutes. We have matched the readings and exercises so that, in total, we think it will take around 2-2.5 hours per week to prepare for the weekly session.

The exercises help you put the concepts from the reading into practice.

Beyond the core posts, there are more materials each week in ‘More to Explore’ — these are all optional and explore the themes of the week in more depth and breadth.

Approximate reading times are given for each of the posts. Generally, we’d prefer you to take your time and think through the readings instead of rushing.

This curriculum was drawn up by staff from the Centre for Effective Altruism, incorporating feedback from others. Ultimately we had to make many judgement calls, and other people would have drawn up a different curriculum.2

How we hope you’ll approach the program #

Taking ideas seriously #

Often, conversations about ideas are recreational: we enjoy batting around interesting thoughts and saying smart things, and then go back to doing whatever we were already doing in our lives. This is a fine thing to do — but at least sometimes, we think we should be asking ourselves questions like:

- “How could I tell if this idea was true?”

- “What evidence would it take to convince me that I was wrong about an idea?”

- “If it is true, what does that imply I should be doing differently in my life? What else does it imply I’m wrong about?”

- “How might this impact my plans for my career/life?”

And, zooming out:

- “Where are my blind spots?”

- “Which important questions should I be thinking about that I’m not?”

- “Do I really know if this idea/plan will help make things better or not?”

Answering these questions can help make our worldviews as accurate and full as possible and, by extension, help us make better decisions about things that we care about.

Disagreements are useful #

When thoughtful people with access to the same information reach very different conclusions from each other, we should be curious about why and we should actively encourage people to voice and investigate where those disagreements are coming from. If, for example, a medical community is divided on whether Treatment A or B does a better job of curing some disease, they should want to get to the bottom of that disagreement, because the right answer matters — lives are at stake. If you start off disagreeing with someone then change your mind, that can be hard to admit, but we think that should be celebrated. Helping conversations become clearer by changing your mind in response to arguments you find compelling will help the community act to save lives more effectively Even if you don’t expect to end up agreeing with the other person, you’ll learn more if you acknowledge that you disagree and try to understand exactly how and why their views disagree with yours.

Be aware of our privilege and the seriousness of these issues #

We shouldn’t lose sight of our privilege in being able to read and discuss these ideas, or that we are talking about real lives. We’re lucky to be in a position where we can have such a large impact, and this opportunity for impact is the consequence of a profoundly unequal world. Also, be conscious of the fact that people in this program come to these discussions with different ideas, backgrounds, and knowledge. Some of these topics can be uncomfortable to talk about — which is one of the reasons they’re so neglected, and so important to talk about — especially when we may have personal ties to some of these areas.

Explore further #

This handbook aims to introduce people to effective altruism in a structured manner. There are far too many relevant topics, ideas, and research for all but a small fraction of them to fit into this very short program. If you are interested in these topics, you may find it very useful to dive into the linked websites, and the websites those sites link to, and so on.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

The Effectiveness Mindset #

“We are always in triage. I fervently hope that one day we will be able to save everyone. In the meantime, it is irresponsible to pretend that we aren’t making life and death decisions with the allocation of our resources. Pretending there is no choice only makes our decisions worse.”

- Holly Elmore , explaining the need to prioritize given our limited resources.

In this chapter we’ll explore why you might want to help others, why it’s so critical to think carefully about how many people are affected by an intervention, and come to terms with the tradeoffs we face in our altruistic efforts.

Key concepts in this chapter include:

- Scope sensitivity: saving ten lives is more important than saving one, and saving a billion lives is a lot more important than saving ten.

- Tradeoffs: Because we have limited time and money, we need to prioritize between different ways to improve the world.

- Scout mindset: We’ll be better able to help others if we’re working together to think clearly and orient towards finding the truth, rather than trying to defend our own ideas. Humans naturally aren’t great at this (aside from wanting to defend our own ideas, we have a host of other biases), but if we want to really understand the world, it’s worth seeking the truth and trying to become clearer thinkers.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Introduction to Effective Altruism #

This is a linkpost for https://www.effectivealtruism.org/articles/introduction-to-effective-altruism

What is effective altruism? #

Effective altruism is a project that aims to find the best ways to help others, and put them into practice.

It’s both a research field , which aims to identify the world’s most pressing problems and the best solutions to them, and a practical community that aims to use those findings to do good.

This project matters because, while many attempts to do good fail, some are enormously effective. For instance, some charities help 100 or even 1,000 times as many people as others, when given the same amount of resources.

This means that by thinking carefully about the best ways to help, we can do far more to tackle the world’s biggest problems.

Effective altruism was formalized by scholars at Oxford University, but has now spread around the world, and is being applied by tens of thousands of people in more than 70 countries.3

People inspired by effective altruism have worked on projects that range from funding the distribution of 200 million malaria nets, to academic research on the future of AI, to campaigning for policies to prevent the next pandemic.

They’re not united by any particular solution to the world’s problems, but by a way of thinking. They try to find unusually good ways of helping, such that a given amount of effort goes an unusually long way. Here are some examples of what they’ve done so far, followed by the values that unite them:

What are some examples of effective altruism in practice? #

Preventing the next pandemic #

Why this issue?

People in effective altruism typically try to identify issues that are big in scale, tractable, and unfairly neglected.4 The aim is to find the biggest gaps in current efforts, in order to find where an additional person can have the greatest impact. One issue that seems to match those criteria is preventing pandemics.

Researchers in effective altruism argued as early as 2014 that, given the history of near-misses, there was a good chance that a large pandemic would happen in our lifetimes.

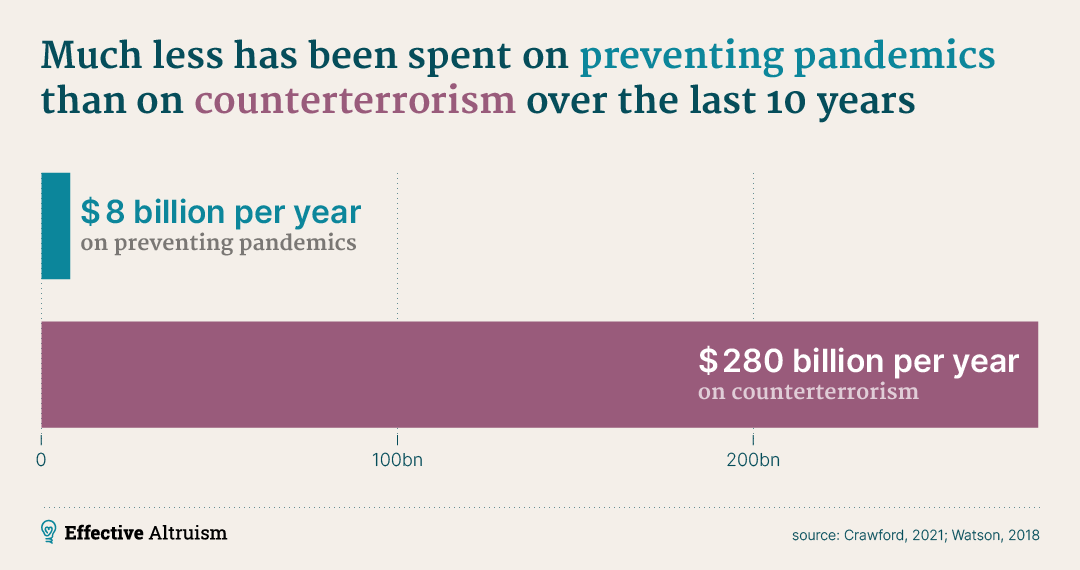

But preparing for the next pandemic was, and remains, hugely underfunded compared to other global issues. For instance, the US invests around $8bn per year preventing pandemics, compared to around $280bn per year spent on counterterrorism over the last decade.5

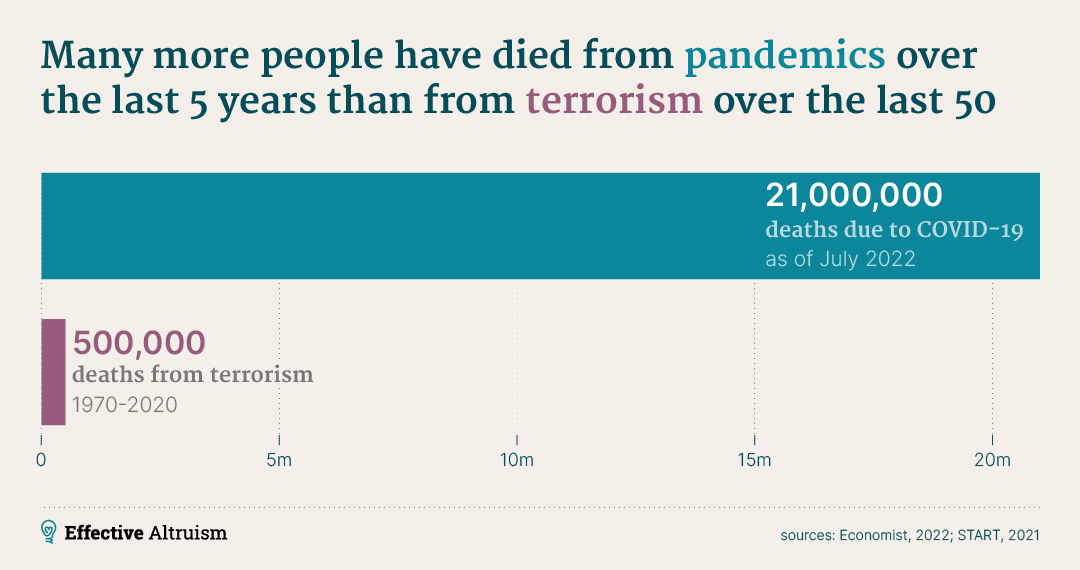

Preventing terror attacks is certainly important. But the scale of the issue seems smaller. For instance, just to focus on the number of deaths, in the last 50 years, around 500,000 people have been killed by terrorism. But over 21 million people were killed by COVID-19 alone6 – or consider the 40 million killed by HIV/AIDS.7

Not to mention, a future pandemic could easily be much worse than COVID-19: there’s nothing to rule out a disease that’s more infectious than the Omicron variant, but that’s as deadly as smallpox. (See more on the comparison in footnote 4.)

In effective altruism, once a big and neglected problem has been identified, the community then looks for solutions that have a chance of making a big contribution to solving the problem, and are neglected by others working on that issue, which brings us to…

Some examples of what’s been done

In 2016 Open Philanthropy – a foundation inspired by effective altruism – became the largest funder of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security , which is one of the few groups doing research to identify better policy responses to pandemics, and was an important group in the response to COVID-19.8

When COVID-19 broke out, members of the community founded 1DaySooner , a non-profit that advocates for human challenge trials. In this type of vaccine trial, healthy volunteers are deliberately infected with the disease, enabling near-instant testing of the vaccine. As one of the only advocates for this intervention, 1DaySooner has signed up over 30,000 volunteers,9 and played an important role in starting the world’s first COVID-19 human challenge trial. This model can be repeated when we face the next pandemic.

Members of the effective altruism community helped to create the Apollo Programme for Biodefense , a multibillion dollar policy proposal designed to prevent the next pandemic.

Providing basic medical supplies in poor countries #

Why this issue?

It’s common to say that charity begins at home, but in effective altruism, charity begins where we can help the most. And this often means focusing on the people who are most neglected by the current system – which is often those who are more distant from us.

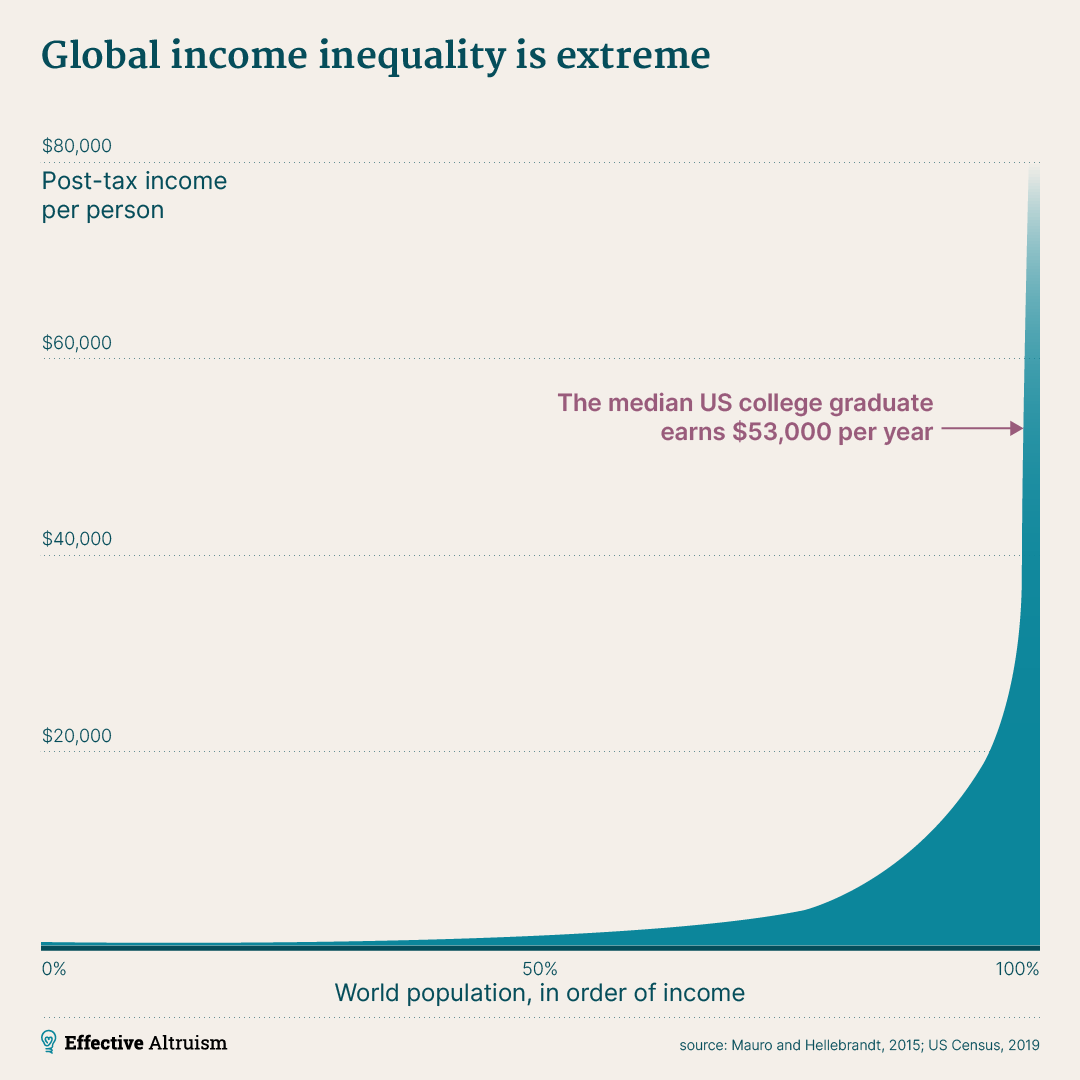

Over 700 million people live on less than $1.90 per day.10

In contrast, an American living near the poverty line lives on 20 times as much, and the average American college graduate lives on about 107 times as much. This places them in the top 1.3% of income, globally speaking.11 (These amounts are already adjusted for the fact that money goes further in poor countries.)

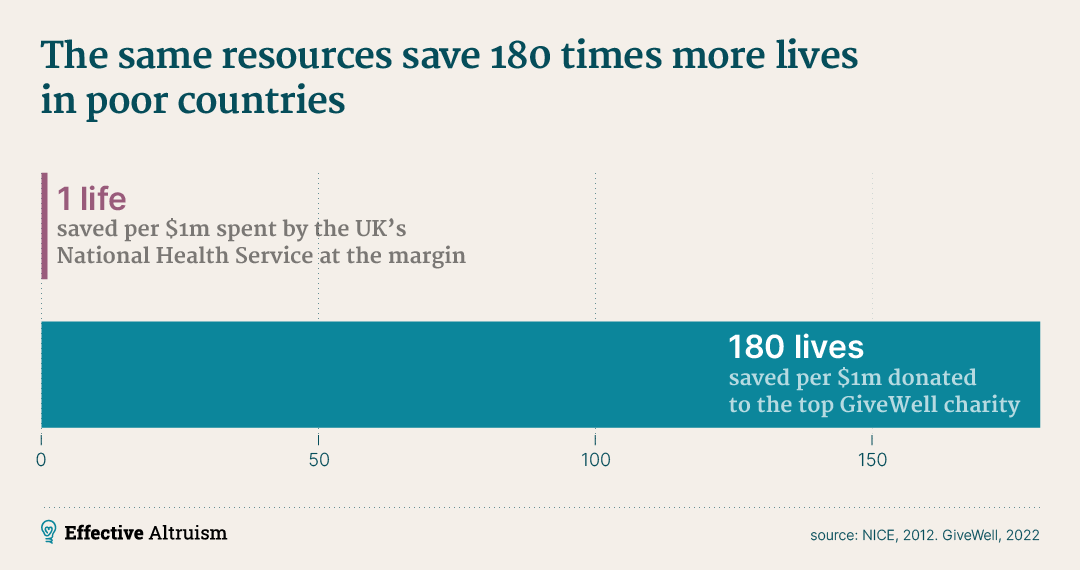

Global inequality is extreme. Because of this, transferring resources to the very poorest people in the world can do a huge amount of good. In richer countries like the US and UK, governments are typically willing to spend over $1 million to save a life.12 This is well worth doing, but in the world’s poorest countries, the cost of saving a life is far lower.

GiveWell is an organization that does in-depth research to find the most evidence-backed and cost-effective health and development projects. It discovered that while many aid interventions don’t work , some, like providing insecticide-treated bednets, can save a child’s life for about $5,500 on average. That’s 180 times less.13

These basic medical interventions are so cheap and effective that even the most prominent aid sceptics agree they’re worthwhile.

Some examples of what’s been done

Over 110,000 individual donors have used GiveWell’s research to contribute more than $1 billion to its recommended charities, supporting organisations like the Against Malaria Foundation , which has distributed over 200 million insecticide-treated bednets. Collectively these efforts are estimated to have saved 159,000 lives.14

In addition to charity, it’s possible to help the world’s poorest people through business. Wave is a technology company founded by members of the effective altruism community, which allows people to transfer money to several African countries faster and several times more cheaply than existing services. It’s especially helpful for migrants sending money home to their families, and has been used by over 800,000 people in countries like Kenya, Uganda and Senegal. In Senegal alone, Wave has saved its users hundreds of millions of dollars in transfer fees – around 1% of the country’s GDP.15

Helping to create the field of AI alignment research #

Why this issue?

People in effective altruism often end up focusing on issues that seem counterintuitive, obscure or exaggerated. But this is because it’s more impactful to work on the issues that are neglected by others (all else equal), and these issues are (almost by definition) going to be unconventional ones. One example is the AI alignment problem.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is progressing rapidly. The leading AI systems are now able to engage in limited conversation, solve college-level maths problems, explain jokes, generate extremely realistic images from text, and do basic coding.16 None of this was possible just ten years ago.

The ultimate goal of the leading AI labs is to develop AI that is as good as, or better than, human beings on all tasks. It’s extremely hard to predict the future of technology, but various arguments and expert surveys suggest that this achievement is more likely than not this century. And according to standard economic models , once general AI can perform at human level, technological progress could dramatically accelerate.

The result would be an enormous transformation, perhaps of a significance similar to or greater than the industrial revolution in the 1800s. If handled well, this transformation could bring about abundance and prosperity for everyone. If handled poorly, it could result in an extreme concentration of power in the hands of a tiny elite.

In the worst case, we could lose control of the AI systems themselves. Unable to govern beings with capabilities far greater than our own, we would find ourselves with as little control over our future as chimpanzees have control over theirs.

This means this issue could not only have a dramatic impact on the present generation, but also on all future generations. This makes it especially pressing from a “longtermist” perspective, a school of thinking which holds that improving the long-term future is a key moral priority of our time.

How to ensure AI systems continue to further human values, even as they become equal (or superior) to humans in their capabilities, is called the AI alignment problem, and solving it requires advances in computer science.

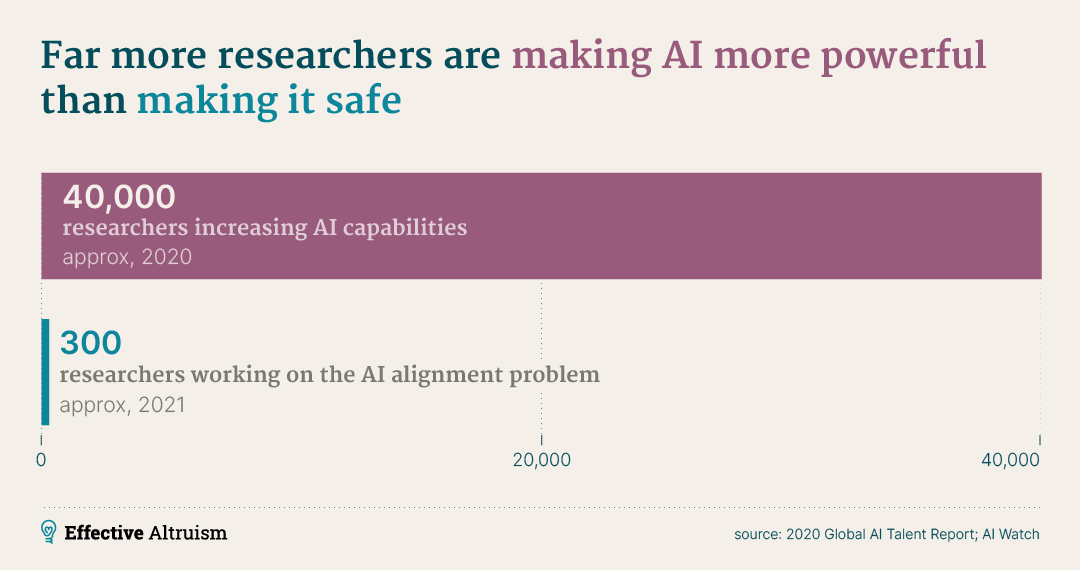

Despite its potentially historic importance, only a couple of hundred researchers work on this problem, compared to tens of thousands working to make AI systems more powerful.17

It’s hard to sum up the case for the issue in a few paragraphs, so if you’d like to explore more, we’d recommend starting here , here and here .

Some examples of what’s been done

One priority is to simply tell more people about the issue. The book Superintelligence was published in 2014, making the case for the importance of AI alignment, and became a New York Times best-seller .

Another priority is to build a research field focused on this problem. For instance, AI pioneer Stuart Russell, and others inspired by effective altruism, founded The Center for Human-Compatible AI at UC Berkeley. This research institute aims to develop a new paradigm of AI development, in which the act of furthering human values is central.

Others have helped to start teams focused on AI alignment at major AI labs such as DeepMind and OpenAI , and outline research agendas for AI alignment, in works such as Concrete Problems in AI Safety .

Ending factory farming #

Why this issue?

People in effective altruism try to extend their circle of concern – not only to those living in distant countries or future generations, but also to non-human animals.

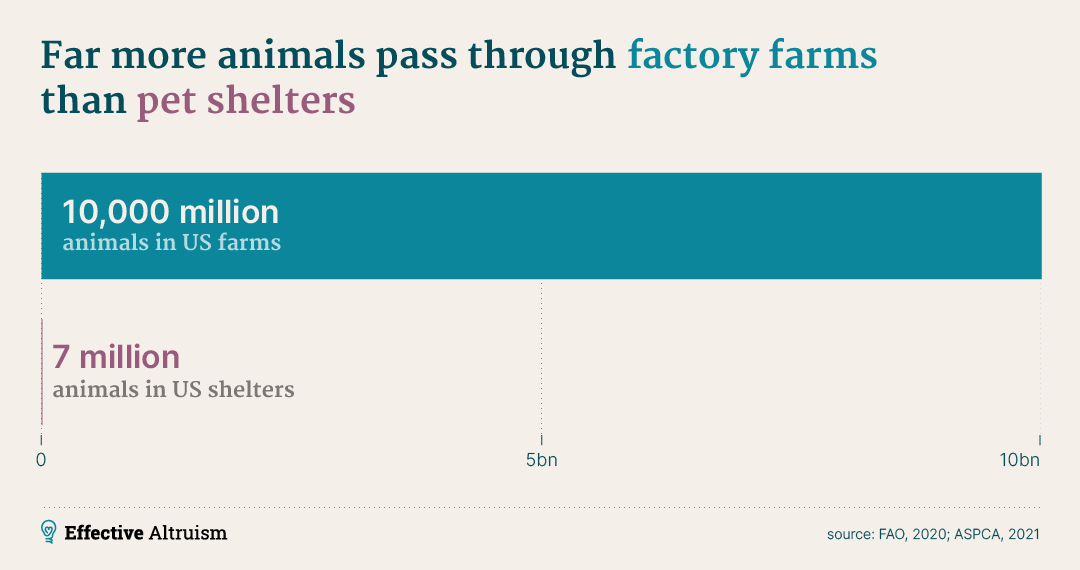

Nearly 10 billion animals live and die in factory farms in the US every year18 – often unable to physically turn around their entire lives, or castrated without anaesthetic.

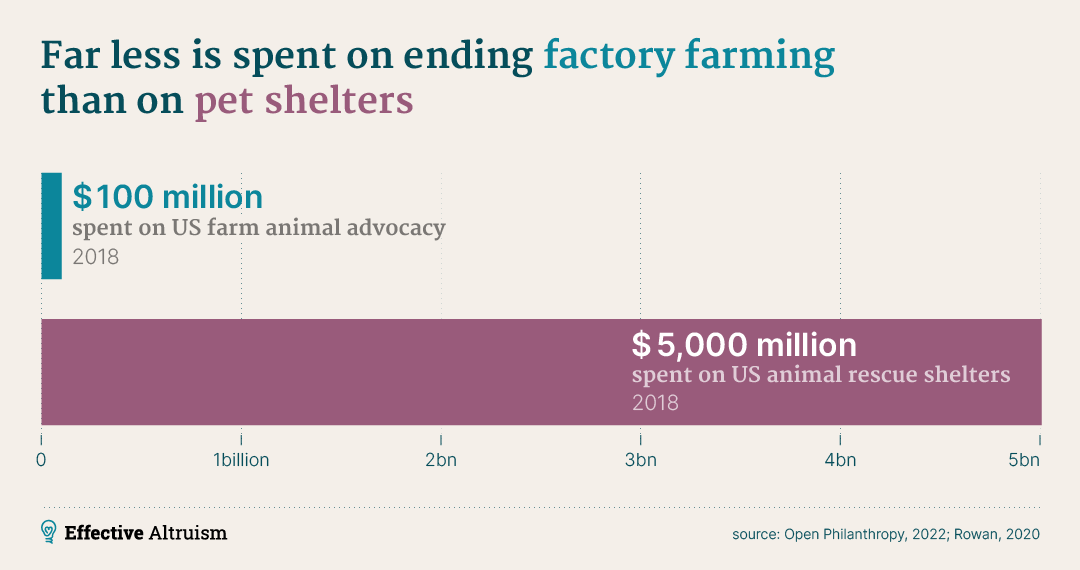

Lots of people agree we shouldn’t make animals suffer needlessly, but most of this attention goes towards pet shelters. In the US, about 1,400 times more animals pass through factory farms than pet shelters.19

Despite this, pet shelters receive around $5 billion per year in the US, compared to only $97 million on advocacy to end factory farming.20

Some examples of what’s been done

One strategy is advocacy. The Open Wing Alliance , which received significant funding from funders inspired by effective altruism, developed a campaign to encourage large companies to commit to stop buying eggs from caged chickens. To date, they have won over 2,200 commitments, and as a result over 100 million birds have been spared from cages.21

Another strategy is to create alternative proteins, which if made cheaper and tastier than factory farmed meat, could make demand disappear, ending factory farming. The Good Food Institute is working to kick-start this industry, helping to create companies like Dao Foods in China and Good Catch in the US, encouraging big business to enter the industry (including JBS, the world’s largest meat company) and securing tens of millions of dollars of government support.22

Open Philanthropy was an early investor in Impossible Foods , which created the Impossible Burger – an entirely vegan burger that tastes much more like meat, and is now sold in Burger King.

Improving decision-making #

Why this issue?

People who want to do good often prefer to directly tackle problems, since it’s more motivating to see the tangible effects of their actions. But what matters is that the world gets better, not that you do it with your own two hands. So people applying effective altruism often try to help indirectly, by empowering others.

One example of this is by improving decision-making. Namely: if key actors — such as politicians, private and third sector leaders, or grantmakers at funding bodies — were generally better at making decisions, society would be in a better position to deal with a whole range of future global problems, whatever they turn out to be.

So, if we can find new, neglected ways to improve the decision-making of important actors, that could be a route to having a big impact. And it seems like there are some promising solutions that could achieve this.

Some examples of what’s been done

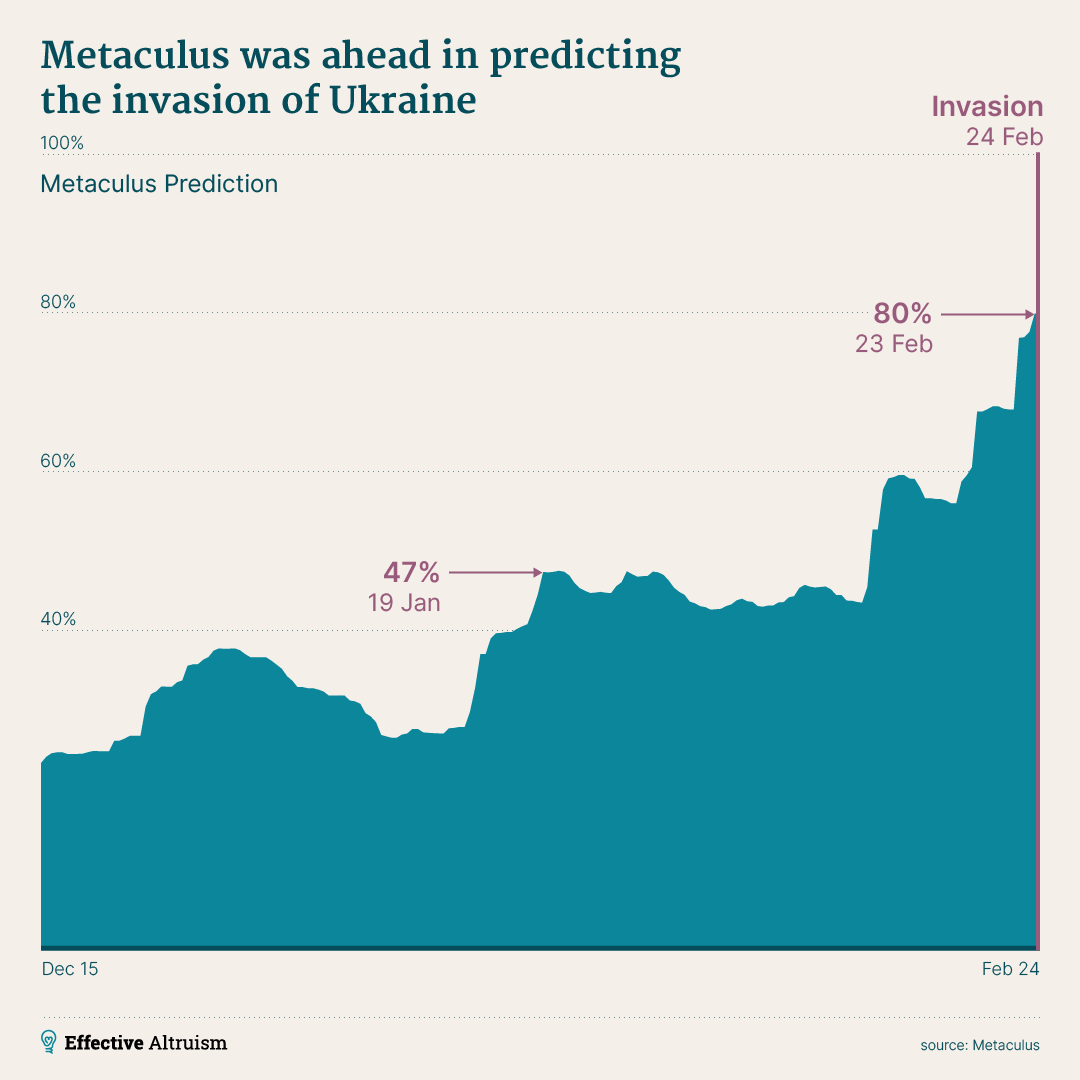

Many global problems are exacerbated by a lack of trustworthy information. Metaculus is a forecasting technology platform that identifies important questions (such as the chance of Russia invading Ukraine), aggregates forecasts made by hundreds of forecasters, and weighs them by their past accuracy. Metaculus gave a probability of a Russian invasion of Ukraine of 47% by mid January 2022, and 80% shortly before the invasion on the 24th of February23 – a time when many pundits, journalists and experts were saying it definitely wouldn’t happen.

The Global Priorities Institute at the University of Oxford does foundational research at the intersection of philosophy and economics into how key decision-makers can identify the world’s most pressing problems. It has helped to create a new academic field of global priorities research, creating a research agenda , publishing tens of papers , and helping to inspire relevant research at Harvard, NYU, UT Austin, Yale, Princeton and elsewhere.

What values unite effective altruism? #

Effective altruism isn’t defined by the projects above, and what it focuses on could easily change. What defines effective altruism are some tentative values and principles that underpin its search for the best ways of helping others:

-

Prioritization: Our intuitions about doing good don’t usually take into account the scale of the outcomes — helping 100 people often makes us feel as satisfied as helping 1000. But since some ways of doing good also achieve dramatically more than others, it’s vital to attempt to use numbers to roughly weigh how much different actions help. The goal is to find the best ways to help, rather than just working to make any difference at all.

-

Impartial altruism: It’s easy — and reasonable — to have special concern for one’s own family, friends or nation. But, when trying to do as much good as possible, it seems that we should give everyone’s interests equal weight, no matter where or when they live. This means focusing on the groups who are most neglected, which usually means focusing on those who don’t have as much power to protect their own interests.

-

Open truthseeking: Rather than starting with a commitment to a certain cause, community or approach, it’s important to consider many different ways to help and seek to find the best ones. This means putting serious time into deliberation and reflection on one’s beliefs, being constantly open and curious for new evidence and arguments, and being ready to change one’s views quite radically.

-

Collaborative spirit: It’s often possible to achieve more by working together, and doing this effectively requires high standards of honesty, integrity, and compassion. Effective altruism does not mean supporting ‘ends justify the means’ reasoning, but rather is about being a good citizen, while working toward a better world.

We’re not totally confident in the above ideas - but we think that they are probably right, and that they are undervalued by much of society. Anyone who is trying to find better ways to help others is participating in effective altruism. This is true no matter how much time or money they want to give, or which issue they choose to focus on.

Effective altruism can be compared to the scientific method. Science is the use of evidence and reason in search of truth – even if the results are unintuitive or run counter to tradition. Effective altruism is the use of evidence and reason in search of the best ways of doing good.

The scientific method is based on simple ideas (e.g. that you should test your beliefs) but it leads to a radically different picture of the world (e.g. quantum mechanics). Likewise, effective altruism is based on simple ideas – that we should treat people equally and it’s better to help more people than fewer – but it leads to an unconventional and ever-evolving picture of doing good.

How can you take action? #

People interested in effective altruism most often attempt to apply the ideas in their lives by:

-

Choosing careers that help tackle pressing problems, or by finding ways to use their existing skills to contribute to these problems, such as by using advice from 80,000 Hours .

-

Donating to carefully chosen charities, such as by using research from GiveWell or Giving What We Can .

-

Starting new organizations that help to tackle pressing problems.

-

Helping to build communities tackling pressing problems.

See a longer list of ways to take action .

The above are not exhaustive. You can apply effective altruism no matter how much you want to focus on doing good, and in any area of your life – what matters is that, no matter how much you want to contribute, your efforts are driven by the four values above, and you try to make your efforts as effective as possible.

Typically, this involves trying to identify big and neglected global problems, the most effective solutions to those problems, and ways you can contribute to those solutions – with whatever time or money you’re willing to give.

By doing this and thinking carefully, you might find it’s possible to have far more impact with those resources. It really is possible to save hundreds of people’s lives over your career. And by teaming up with others in the community, you can play a role in tackling some of the most important issues civilization faces today.

Four Ideas You Already Agree With #

This is a linkpost for https://www.givingwhatwecan.org/blog/four-things-you-already-agree-with-effective-altruism

Here are four ideas that you probably already agree with. Three are about your values, and one is an observation about the world. Individually, they each might seem a bit trite or self-evident. But taken together, they have significant implications for how we think about doing good in the world.

The four ideas are as follows:

- It’s important to help others — when people are in need and we can help them, we think that we should. Sometimes we think it might even be morally required: most people think that millionaires should give something back. But it may surprise you to learn that those of us on or above the median wage in a rich country are typically part of the global 5% 24 — maybe we can also afford to give back too.

- People 25 are equal — everyone has an equal claim to being happy, healthy, fulfilled and free , whatever their circumstances. All people matter, wherever they live, however rich they are, and whatever their ethnicity, age, gender, ability, religious views, etc.

- Helping more is better than helping less — all else being equal, we should save more lives, help people live longer, and make more people happier. Imagine twenty sick people lining a hospital ward, who’ll die if you don’t give them medicine. You have enough medicine for everyone, and no reason to hold onto it for later: would anyone really choose to arbitrarily save only some of the people if it was just as easy to save all of them?

- Our resources are limited — even millionaires have a finite amount of money they can spend. This is also true of our time — there are never enough hours in the day. Choosing to spend money or time on one option is an implicit choice not to spend it on other options (whether we think about these options or not).

I think that these four ideas are all pretty uncontroversial. I think it seems pretty intuitive that we should help people in need if we can; that we shouldn’t arbitrarily preference some groups of people over others; that we would prefer to help more people if given the option; and that we don’t have infinite time and money.

In fact I’d go further — I’d say that we’d feel pretty uncomfortable trying to defend the alternative positions if we were talking to someone, namely:

- Helping others in need isn’t morally required, important, or even that good

- It’s OK to value people differently based on arbitrary differences like race, gender, ability etc.

- It doesn’t matter if some people die even if it doesn’t really cost us anything extra to save their lives

- We have unlimited resources

See what I mean?

We don’t have infinite money, so we always need to choose which worthy cause to support.

So if we agree that these four ideas embody important values — and I think that they do — then there are big implications for how we should think about doing good. In fact, it means that the way we typically think about doing good is wrong.

In order to be true to these values, we need to think about how we can help the most people with our limited resources.

This is important, because there are some causes where we can make a big impact for a small amount of money. In fact the best options are much, much better than the average — sometimes hundreds of times better. That might mean the difference between helping one person, and helping hundreds of people for exactly the same amount of time or money.

Because a charity chosen at random is almost certainly not making as big an impact as the most effective charities (and let’s face it, many causes we choose to support tend to be the result of either random chance, or systemic factors that mean we’re only exposed to certain causes).

And this matters, because if we don’t choose well, then we’re either not giving people equal consideration (that is, implicitly discriminating against some groups of people), or we’re not helping as many people as we can (that is, allowing extra people to suffer or die, even though we could potentially help them).

So, at first, every worthy cause — from cancer research, to climate justice, to animal sanctuaries, to preventing easily treatable but unpronounceable diseases in places that we’ll probably never visit — should be on the table… except that we also think it’s better to help more people and we understand that we don’t have the resources to help everyone. So we should first focus on the causes where we can help the most people for our limited time and money, not just on those that we happen to have already heard about.

Trying to be cause-neutral can be a really hard thing to do. Most people have first-hand experience of loss: I’ve lost two relatives to leukaemia; watched as the disease consumed their bodies and the pain meds fogged their minds; lived through the shared grief of their passing. It’s entirely reasonable that this makes us want to donate to organisations trying to solve the specific problem or cure the particular disease that has robbed us of our loved ones. We’re empathetic creatures, and we don’t want other people to experience the same suffering, or for their loved ones to experience the same grief.

But if we care about treating people equally, we should also care about treating their experiences equally. There’s not a really good reason that I should prefer averting the death, disability, and suffering caused by a particular disease (like leukaemia) any more than I should care about suffering caused by malaria, tuberculosis, traffic accidents, or anything else. What matters is that lives are cut short, parents are deprived of their children, people are living in pain. Caring about equality means treating all death and suffering as a tragedy, not just that caused by specific diseases that we — by cruel twists of fate that thrust them into our field of view — happen to notice.

Making these decisions is really, really hard. But there is a set of thinking tools we can use to help us. This way of thinking is called effective altruism . It’s basically the same as regular altruism (in that it emphasises the importance of helping other people) — the word ’effective’ just means trying to think clearly about how your actions can help the most people , or do the most good.

I see effective altruism as a way of being able to better live up to values that we already hold.

This way of thinking is applicable to any way that we might want to do good — whether that be agitating for political change, choosing where we donate our money, or how to have a big impact with our careers.

In a world where there are so many worthy causes we could work on, it gives us a way out of decision paralysis, by systematically looking for ways to do the most good with our limited time and money.

It asks us to face up to some hard choices. But remember, we’re making these choices anyway, whether we think about them or not. So even though it might be hard to not donate to something that seems really important — whether for personal reasons, or because you’re convinced by a charity’s marketing pitch — remember that you’re always trading off against other worthy causes.

Here’s an example of this in action. The typical person in the UK donates around £6,700 ($9,600USD)26 over the course of their working lifetimes. For this money we could fund the distribution of around 1,900 mosquito nets 27 (likely preventing around 200children from becoming really, really sick from malaria28, and probably saving at least two or three lives ). However, most voluntary donations go to domestic medical charities.29 The UK’s National Health Service considers it good value to save one year of healthy life for around £25,000. 30It’s highly unlikely that a domestic charity will beat this figure, so the typical donor’s impact is going to be many, many times less than it could otherwise be. Remember, just because we don’t think about these choices, doesn’t mean that they’re not there.

So please, think carefully about these ideas — the importance of altruism, equality, and doing as much as we can with our scarce resources — and see if they make sense to you.

If they do, then the next time you think about how to make the world a better place, give voice to these values by thinking effectively , as well as altruistically.

Some resources for learning more about effective altruism:

- What is Effective Altruism?

- This really quick summary of effective altruism

- The Wikipedia entry on effective altruism

- Doing Good Better by Will MacAskill

- The Effective Altruism Handbook

Some actions you can take that we think are really effective

- Donate to a charity recommended on the basis of its impact and cost-effectiveness — check out our Top Charities , and GiveWell’s recommendations . If you’d like to support charities that increase the welfare of non-human animals effectively, check out Animal Charity Evaluators .

- Pledge to keep donating over the course of your lifetime — 8,438 people (and counting) have pledged to donate 10% of their lifetime income to the most effective charities, and 798 have made pledges of 1% or more of their income for a custom period.

- Choose a career that’s really high-impact by reading career advice from 80,000 Hours

- Start a chapter or discussion group in your local area or at your university, and get other people interested in making a bigger difference

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

The world is much better. The world is awful. The world can be much better. #

(Cross-posted from Our World in Data .)

The world is much better. The world is awful. The world can be much better. All three statements are true.

Here I focus on child mortality, but the same can be said for many aspects of global development. There are many aspects of development for which it is true that things have improved over time and are terrible still, and for which we know that things can get better.

The world is awful #

In the visualization below, I present three scenarios of child deaths. The blue bar represents the actual number of child deaths per year today. Of the 141 million children born every year, 3.9% die before their 5th birthday. This means that every year, 5.5 million children die; on average, 15,000 children die every day. 31

Clearly, a world where such tragedy happens is an awful world.

The world is much better #

The big lesson of history is that things change. The scale of these changes is hard to grasp. The living conditions in today’s poorest countries are now in many ways much better than they were even in the richest countries of the past: Child mortality in today’s worst-off places is between 10-13% ; in all regions of the world it was more than three times as high [ 30-50% ] until a few generations ago. It’s estimated that at the beginning of the 19th century, 43% of the world’s children died by the age of five. If we still suffered the poor health of our ancestors, more than 60 million children would die every year — 166,000 every day. 32

This is what the red bar represents in the visualization below.

If you want to see how child mortality has changed, read Hannah Ritchie’s post: From commonplace to rarer tragedy — declining child mortality across the world

Such large improvements are not limited to health; the same is true across other aspects of life (as I show in my short history of living conditions ). In a number of fundamental aspects (obviously not all ), we have achieved very substantial progress and know that much more is possible. These aspects also include education , political freedom , violence , poverty , nutrition , and some aspects of environmental change.

What we learn from this is that it is possible to change the world. I believe that one of the most important facts to know about our world is that we can make a difference.

(You can see a larger version of this graph here .)

The world can be much better #

Progress over time shows that it was possible to change the world in the past. But what do we know about what is possible for the future? Were we born at an unlucky time in modern history, in which global progress has come to a halt?

Studying the global data suggests that the answer is no. One way to see this is to look at those places in the world with the best living conditions. The inequality in living conditions in the world today shows that there is much work left to do. If health across all countries of the world was equal, it would not be possible to really know whether further improvements are possible or how to achieve them. But the fact that some places have already achieved much better child health leaves no doubt: Better child health than the global average is not just a possibility, but already a reality.

So what would global child mortality be if children around the world became as well off as the children in those places where children are healthiest today?

The dark green bar in the visualization shows the answer. The region with the lowest child mortality is the European Union. The average in the European Union (0.41%) is 10 times lower than the global average (3.9%).

In the EU, 1 in 250 children die, whilst globally the figure is 1 in 25. If children around the world were as well off as children in the EU, 5 million fewer children would die every year.

Of course, a child mortality rate of 1 in 250 is still too high. It will be a major achievement if the world as a whole catches up to that level of health, but in the healthiest places we should also try to push the boundaries of what has been shown to be possible.

We should certainly not make the mistake of believing that it would be easy to reduce the global child mortality rate to that of the EU. For a society to achieve such good health, many development aspects have to improve; today’s best-off countries achieved two centuries of slow, sustained economic growth that bought the infrastructure (housing, sanitation , public health measures) necessary for good health.

But while a better world cannot be achieved overnight, we learn what is possible from the best-off regions; in this sense, we know that these 5 million annual deaths are preventable. The fact that child mortality in entire world regions is tenfold lower than in the world as a whole shows us that it is possible to make the world a better place.

The world is terrible; this is why we need to know about positive change #

It’s easier to scare people than to instill confidence in them, and many writers on global development report on how awful the world is. I agree that it is important that we know what is wrong with the world, but given the scale of what we have achieved already and what is possible for the future, I think it’s irresponsible to only report on how dreadful our situation is.

The world is much better. The world is awful. The world can be much better. We have to study the data to know all three perspectives on global living conditions. When we do this, these facts are impossible to miss. But the facts of how the world is changing are not known to most of us because many of the writers that report on how the world is changing do not take the data seriously. This needs to change.

What we have to achieve as writers on global change is to convey both perspectives at the same time: We need to know how terrible the world still is and that a better world is possible. This is what I hope to do.

If we had achieved the best of all possible worlds, I wouldn’t spend my life writing and researching about how we got here. What keeps me going is to share the knowledge that change is possible — though not inevitable — and the wealth of knowledge that researchers around the world have acquired on how to make a better world for everyone.

We know that it is possible to make the world a better place because we already did it. It is because the world is terrible still that it’s so important to write about how, in several important aspects, the world became a better place.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

On Caring #

This version of the essay has been lightly edited. You can find the original _ _here__ .

1 #

I’m not very good at feeling the size of large numbers. Once you start tossing around numbers larger than 1,000 (or maybe even 100), the numbers just seem “big”.

Consider Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. If you told me that Sirius is as big as a million Earths, I would feel like that’s a lot of Earths. If, instead, you told me that you could fit a billion Earths inside Sirius … I would still just feel like that’s a lot of Earths.

The feelings are almost identical. In context , my brain grudgingly admits that a billion is a lot larger than a million, and puts forth a token effort to feel like a one-billion-Earths-sized star is bigger than a one-million-Earths-sized star. But out of context — if I weren’t anchored at “a million” when I heard “a billion” — both of these numbers just feel vaguely large.

I feel a little respect for the bigness of numbers if you pick really, really large numbers. If you say, “One followed by 100 zeroes,” then this feels a lot bigger than a billion. But it certainly doesn’t feel (in my gut) like it’s 10 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 times bigger than a billion. Not in the way that four apples internally feels like twice as many as two apples. My brain can’t even begin to wrap itself around this sort of magnitude differential.

This phenomenon is related to scope insensitivity , and it’s important to me because I live in a world where sometimes the things I care about are really, really numerous.

For example, billions of people live in dire poverty , with hundreds of millions of them deprived of basic needs and/or dying from disease. And though most of them are out of my sight, I still care about them.

The loss of a human life with all its joys and all its sorrows is tragic no matter what the cause, and the tragedy is not reduced simply because I was far away, or because I did not know of it, or because I did not know how to help, or because I was not personally responsible.

Knowing this, I care about every single individual on this planet. The problem is, my brain is simply incapable of taking the amount of caring I feel for a single person and scaling it up by a billion times. I lack the internal capacity to feel that much. My care-o-meter simply doesn’t go up that far.

And this is a problem.

2 #

It’s a common trope that courage isn’t about being fearless; it’s about being afraid but doing the right thing anyway. In the same sense, caring about the world isn’t about having a gut feeling that corresponds to the amount of suffering in the world; it’s about doing the right thing anyway. Even without the feeling.

My internal care-o-meter was calibrated to deal with about 150 people , and it simply can’t express the amount of caring that I have for billions of sufferers. The internal care-o-meter just doesn’t go up that high.

Humanity is playing for unimaginably high stakes. At the very least, there are billions of people suffering today. At the worst, there are quadrillions (or more) potential humans, transhumans, or posthumans whose existence depends upon what we do here and now. All the intricate civilizations that the future could hold, the experience and art and beauty that is possible in the future, depends upon the present.

When you’re faced with stakes like these, your internal caring heuristics — calibrated on numbers like 10 or 20, and maxing out around 150 — completely fail to grasp the gravity of the situation.

Saving a person’s life feels great , and it would probably feel just about as good to save one life as it would feel to save the world . It surely wouldn’t be many billion times more of a high to save the world, because your hardware can’t express a feeling a billion times bigger than the feeling of saving a person’s life. But even though the altruistic high from saving someone’s life would be shockingly similar to the altruistic high from saving the world, always remember that behind those similar feelings there is a whole world of difference.

Our internal care-feelings are woefully inadequate for deciding how to act in a world with big problems.

3 #

There’s a mental shift that happened to me when I first started internalizing scope insensitivity. It is a little difficult to articulate, so I’m going to start with a few stories.

Consider Alice, a software engineer at Amazon in Seattle. Once a month or so, college students show up on street corners with clipboards, looking ever more disillusioned as they struggle to convince people to donate to Doctors Without Borders . Usually, Alice avoids eye contact and goes about her day, but this month they finally manage to corner her. They explain Doctors Without Borders, and she actually has to admit that it sounds like a pretty good cause. She ends up handing them $20 through a combination of guilt, social pressure, and altruism, and then rushes back to work. (Next month, when they show up again, she avoids eye contact.)

Now consider Bob, who has been given the Ice Bucket Challenge by a friend on Facebook. He feels too busy to do the challenge, and instead just donates $100 to ALSA .

Now consider Christine, who is in the college sorority ΑΔΠ. ΑΔΠ is engaged in a competition with ΠΒΦ (another sorority) to see who can raise the most money for the National Breast Cancer Foundation in a week. Christine has a competitive spirit and gets engaged in fundraising, and gives a few hundred dollars herself over the course of the week (especially at times when ΑΔΠ is especially behind).

All three of these people are donating money to charitable organizations, and that’s great. But notice that there’s something similar in these three stories: These donations are largely motivated by a social context. Alice feels obligation and social pressure. Bob feels social pressure and maybe a bit of camaraderie. Christine feels camaraderie and competitiveness. These are all fine motivations, but notice that these motivations are related to the social setting , and only tangentially to the content of the charitable donation.

If you took Alice or Bob or Christine aside and asked them why they aren’t donating all of their time and money to these causes that they apparently believe are worthwhile, they’d look at you funny and they’d probably think you were being rude (with good reason!). If you pressed, they might tell you that money is a little tight right now, or that they would donate more if they were a better person.

But the question would still feel kind of wrong. Giving all of your money away is just not what you do with money. We can all say out loud that people who give all of their possessions away are really great, but behind closed doors we all know that those people are crazy. (Good crazy, perhaps, but crazy all the same.)

This is a mindset that I inhabited for a while. But there’s an alternative mindset that can hit you like a freight train when you start internalizing scope insensitivity.

4 #

Consider Daniel, a college student. Shortly after the Deepwater Horizon BP oil spill, he encounters one of those people with the clipboards on the street corners, soliciting donations to the World Wildlife Foundation . They’re trying to save as many oiled birds as possible. Normally, Daniel would simply dismiss the charity as Not The Most Important Thing, or Not Worth His Time Right Now, or Somebody Else’s Problem, but this time Daniel has been thinking about how his brain is bad at numbers and decides to do a quick sanity check.

He pictures himself walking along the beach after the oil spill and encountering a group of people cleaning birds as fast as they can. They simply don’t have the resources to clean all of the available birds. A pathetic young bird flops toward his feet, slick with oil, eyes barely able to open. He kneels down to pick it up and help it onto the table. One of the bird-cleaners informs him that they won’t have time to get to that bird themselves, but he could pull on some gloves and could probably save the bird with three minutes of washing.

Daniel decides that he would spend three minutes of his time to save the bird, and that he would also be happy to pay at least $3 to have someone else spend a few minutes cleaning the bird. He introspects and finds that this is not just because he imagined a bird right in front of him: He feels that it is worth at least three minutes of his time (or $3) to save an oiled bird in some vague, platonic sense.

And, because he’s been thinking about scope insensitivity, he expects his brain to misreport how much he actually cares about large numbers of birds; the internal feeling of caring can’t be expected to line up with the actual importance of the situation. So instead of just asking his gut how much he cares about de-oiling lots of birds, he shuts up and multiplies.

Thousands and thousands of birds were oiled by the BP spill alone. After shutting up and multiplying, Daniel realizes (with growing horror) that the amount he actually cares about oiled birds is lower-bounded by two months of hard work and/or fifty thousand dollars. And that’s not even counting wildlife threatened by other oil spills .

And if he cares that much about de-oiling birds , then how much does he actually care about factory farming, nevermind hunger, or poverty, or sickness? How much does he actually care about wars that ravage nations? About neglected, deprived children? About the future of humanity? He actually cares about these things to the tune of much more money than he has, and much more time than he has.

For the first time, Daniel sees a glimpse of how much he actually cares, and how poor a state the world is in.

This has the strange effect that Daniel’s reasoning goes full-circle, and he realizes that he actually can’t care about oiled birds to the tune of 3 minutes or $3 — not because the birds aren’t worth the time and money (in fact, he thinks that the economy produces things priced at $3 which are worth less than a bird’s survival), but because he can’t spend his time or money on saving the birds. The opportunity cost suddenly seems far too high: There is too much else to do! People are sick and starving and dying! The very future of our civilization is at stake!

Daniel doesn’t wind up giving $50,000 to the World Wildlife Fund, and he also doesn’t donate to the ALS Association or the National Breast Cancer Foundation. But if you ask Daniel why he’s not donating all his money, he won’t look at you funny or think you’re rude. He’s left the place where you don’t care far behind, and has realized that his mind was lying to him the whole time about the gravity of the real problems.

Now he realizes that he can’t possibly do enough. After adjusting for his scope insensitivity (and the fact that his brain lies about the size of large numbers), even the “less important” causes like the WWF suddenly seem worthy of dedicating a life to. Wildlife destruction and ALS and breast cancer are suddenly all problems that he would move mountains to solve — except he’s finally understood that there are just too many mountains, and ALS isn’t the bottleneck, and AHHH HOW DID ALL THESE MOUNTAINS GET HERE?

In the original mindstate, the reason he didn’t drop everything to work on ALS was because it just didn’t seem … pressing enough. Or tractable enough. Or important enough. Kind of. These are sort of the reason, but the real reason is more that the concept of “dropping everything to address ALS” never even crossed his mind as a real possibility. The idea was too much of a break from the standard narrative. It wasn’t his problem.

In the new mindstate, everything is his problem. The only reason he’s not dropping everything to work on ALS is because there are far too many things to do first.

Alice and Bob and Christine usually aren’t spending time solving all the world’s problems because they forget to see them. If you remind them — put them in a social context where they remember how much they care (hopefully without guilt or pressure) — then they’ll likely donate a little money.

By contrast, Daniel and others who have undergone the mental shift aren’t spending time solving all the world’s problems because there are just too many problems. (Daniel hopefully goes on to discover movements like effective altruism and starts contributing toward fixing the world’s most pressing problems.)

5 #

I’m not trying to preach here about how to be a good person. You don’t need to share my viewpoint to be a good person (obviously).

Rather, I’m trying to point at a shift in perspective. Many of us go through life understanding that we should care about people suffering far away from us, but failing to. I think that this attitude is tied, at least in part, to the fact that most of us implicitly trust our internal care-o-meters.

The “care feeling” isn’t usually strong enough to compel us to frantically save everyone dying. So while we acknowledge that it would be virtuous to do more for the world, we think that we can’t , because we weren’t gifted with that virtuous extra-caring that prominent altruists must have.

But this is an error — prominent altruists aren’t the people who have a larger care-o-meter; they’re the people who have learned not to trust their care-o-meters.

Our care-o-meters are broken. They don’t work on large numbers. Nobody has one capable of faithfully representing the scope of the world’s problems. But the fact that you can’t feel the caring doesn’t mean that you can’t do the caring.

You don’t get to feel the appropriate amount of “care” in your body. Sorry — the world’s problems are just too large, and your body is not built to respond appropriately to problems of this magnitude. But if you choose to do so, you can still act like the world’s problems are as big as they are. You can stop trusting internal feelings to guide your actions and switch over to manual control.

6 #

This, of course, leads us to the question of “What the hell do you do, then?”

And I don’t really know yet. (Though I’ll plug the Giving What We Can pledge , GiveWell , MIRI , and The Future of Humanity Institute as a good start.)

I think that at least part of it comes from a certain sort of desperate perspective. It’s not enough to think you should change the world — you also need the sort of desperation that comes from realizing that you would dedicate your entire life to solving the world’s 100th biggest problem if you could, but you can’t, because there are 99 bigger problems you have to address first.

I’m not trying to guilt you into giving more money away — becoming a philanthropist is really, really hard. (If you’re already a philanthropist, then you have my respect and my affection.) First it requires you to have money, which is uncommon, and then it requires you to throw that money at distant, invisible problems , which is not an easy sell to a human brain. Akrasia is a formidable enemy. And more importantly, guilt doesn’t seem like a good long-term motivator: If you want to join the ranks of people saving the world, I would rather you join them proudly. There are many trials and tribulations ahead, and we’d do better to face them with our heads held high.

7 #

Courage isn’t about being fearless; it’s about being able to do the right thing even if you’re afraid.

And similarly, addressing the major problems of our time isn’t about feeling a strong compulsion to do so. It’s about trying to address them even when internal compulsion utterly fails to capture the scope of the problems we face.

It’s easy to look at especially virtuous people — Gandhi, Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela — and conclude that they must have cared more than we do. But I don’t think that’s the case.

Nobody gets to comprehend the scope of these problems. The closest we can get is doing the multiplication: finding something we care about, putting a number on it, and multiplying. And then trusting the numbers more than we trust our feelings.

Because our feelings lie to us.

When you do the multiplication, you realize that addressing global poverty and building a brighter future deserve more resources than currently exist. There is not enough money, time, or effort in the world to do what we need to do.

There is only you, and me, and everyone else who is trying anyway.

8 #

You can’t actually feel the weight of the world. The human mind is not capable of that feat.

But sometimes, you can catch a glimpse.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Scope insensitivity: failing to appreciate the numbers of those who need our help #

This is a linkpost for https://www.animal-ethics.org/scope-insensitivity-failing-to-appreciate-the-numbers-of-those-who-need-our-help/

Consider one billion animals. Now consider one trillion animals. The second number is vastly higher. However, it is difficult for many people to have a clear idea of what the magnitude of that difference is. As a result of this, we often fail to assess properly what we should do when large numbers of individuals are affected.

This is due to a cognitive bias called scope insensitivity. It is also known as scope neglect. It means we don’t realize the real scope of a certain quantity. So when we compare two different quantities we fail to notice the difference between them. This usually happens when those quantities are very large.

Scope insensitivity causes people not to adjust their valuation of an issue in proportion to the size or scale of it.33 Scope insensitivity especially impairs our judgments about helping animals because of the massive amount of animal suffering and death.

Scope insensitivity probably occurs due to our inability to visualize, or otherwise imagine, such large numbers. When we are not able to visualize a situation where a large number of individuals need our help, we must instead understand it at a more abstract quantitative level. This rarely triggers a strong emotional reaction in us, such as we get when we help a particular number of individuals we can visualize. Importantly from an ethical standpoint, it has been argued that too little emotional involvement can lead to a failure to react.34 Because of that, scope insensitivity may contribute to non-optimal decision outcomes in situations where the goal is to improve the situation of as many individuals as possible.35 In fact, sometimes those decisions are very poor ones.

An example: how much would you be willing to pay to save a certain number of animals? #

In the original study that assessed this phenomenon, different groups of people were asked how much they would pay to save either a group of 2,000 birds, another of 20,000 birds, or a group of 200,000 birds from drowning in ponds polluted with oil. Assuming people’s intention was truly to help as many birds as possible, they should value each of their lives equally. If they were looking clearly at the issue, we would expect them to be willing to pay 10 times as much for the second group as for the first group, and 100 times as much for the third group as for the first group. In fact, the results showed that willingness to pay did not increase in proportion with the number of birds saved.36 Participants were willing to pay $80 to save 2,000 birds. They were willing to pay $78 to save 20,000. That is, 2$ less to save 18,000 more individuals. Finally, they were willing to pay $88 to save 200,000. Thus, only 8$ extra to help 180,000 more birds. That suggests that participants valued each individual bird less the more of them there were to save (4, 0.39, and 0.044 cents, respectively).

This is a clear case of scope insensitivity. The fact that participants were only willing to pay $80 to save a group of 2,000 birds is very problematic in its own right. Yet, the scope insensitivity they showed is also worrisome, given how it impairs our moral judgment when confronted when very large numbers of individuals in need of our help.

A psychological explanation of the scope insensitivity bias #

One explanation of how scope insensitivity occurs has to do with how we often represent things in order to understand them, which is called representativeness heuristic (heuristics, often referred to as “mental shortcuts,” are ways to easily solve problems, especially when we have to make a decision). The representativeness heuristic describes people’s tendency to imagine a simple, normal example of the type of problem being presented to them, rather than picturing all the specific details of the case in question, which may be very complex. Like all heuristics, this can be a useful mental shortcut, since it reduces problems to a more manageable size, thereby simplifying our information processing and decision-making efforts.

However, as the example above shows, this mechanism can be inappropriate to use in many situations. In the example, people tended to imagine or visualize roughly the same thing, so their natural empathy was stimulated to roughly the same degree by all of them, despite the significant differences in the three numbers.37

If a person’s aim is to feel good, or to avoid feeling bad, through some altruistic behavior (like a charitable donation), they do not have an incentive to check whether they are actually doing some good or just seeming to do so – because it feels the same in each case and that is their bottom line.38 In addition, being confronted with too much suffering can lead to what is often called the collapse of compassion , a defense mechanism that reduces or eliminates our sensitivity to the harms others suffer when we are faced with massive amounts of suffering.39 As a result, people will tend not to do the cognitive work of adjusting for scope neglect.

That being said, part of the problem may consist in people simply failing to notice their bias, meaning that they would adjust their decisions if only they were informed about its existence.40

In addition, due to the key role of emotions in moral intuitions and in decision-making processes,41 it has been shown that raising emotional concern for individual victims of large-scale suffering increases overall concern. It has also been shown that personal stories and visual images motivate helping responses more than using abstract numerical figures and statistics. These vivid descriptions of single individuals in need can be useful to keep emotions aroused when large numbers of individuals are concerned.42 This is a way of trying to adjust advocacy to the existence of cognitive biases. It is problematic, however, as we are not always going to be able to do this. For instance, we may not be able to provide such stories when we consider possible new forms of suffering in the future.

Scope insensitivity and our failure to help animals in the wild in need of aid #

Scope insensitivity is especially problematic when it biases us away from helping animals in the wild. There is an astronomical amount of suffering constantly going on in the natural world. For example, the leading estimate as to the number of insects in the wild is 1018 .43 A majority of these animals die a painful death in their first days of life. This amount of suffering simply dwarfs any that we are used to dealing with or thinking about.

In order to react properly to these magnitudes, we should be prepared to adjust our initial emotional reaction based on our more abstract understanding of the quantity. For example, we can try to imagine the largest number of insects that we can and then try to remember how much bigger of an issue it is than we can possibly imagine.

Giving everyone equal consideration #

The equivalent suffering of each individual should be given the same consideration. Unfortunately, however, the valuations of individual lives and suffering are often guided by moral intuitions which are highly influenced by non-rational mechanisms and emotions that can lead to partial judgments. As we have seen here, one of these mechanisms is scope insensitivity.

Hence, we cannot rely solely on our more immediate decision-making processes when making moral judgments involving large numbers of individuals. We must bear this in mind and try to adjust for the errors our decision-making process will run into because of this bias.

Further readings #

Baron, J. & Greene, J. (1996) “Determinants of insensitivity to quantity in valuation of public goods: Contribution, warm glow, budget constraints, availability, and prominence”, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied , 2, pp. 107-125.

Bruers, S. (2016) “ A rational approach to improve worldwide well-being ”, The Rational Ethicist , februari 12 [accessed on 20 May 2017].

Bruers, S. (2017) “ Moral illusions and wild animal suffering neglect ”, The Rational Ethicist , juli 20 [accessed on 18 May 2017].

Cameron, C. D. & Payne, B. K. (2011) “Escaping affect: How motivated emotion regulation creates insensitivity to mass suffering”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, pp. 1-15.

Carson, R. T. & Mitchell, R. C. 1995) “Sequencing and nesting in contingent valuation surveys”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management , 28, pp. 155-173.

Desmeules, R.; Bechara, A. & Dubé, L. (2008) “Subjective valuation and asymmetrical motivational systems: Implications of scope insensitivity for decision making”, Journal of Behavioral Decision Makin g, 21, pp. 211-224.

Dickert, S.; Västfjäll, D.; Kleber, J. & Slovic, P. (2015) “ Scope insensitivity: The limits of intuitive valuation of human lives in public policy ”, Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition , 4, pp. 248-255 [accessed on 16 May 2017].

Erick, S. F. & Fischhoff, B. (1998) “Scope (in)sensitivity in elicited valuations”, Risk Decision and Policy , 3, pp. 109-123.

Fetherstonhaugh, D.; Slovic, P.; Johnson, S. & Friedrich, J. (1997) “Insensitivity to the value of human life: A study of psychophysical numbing”, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty , 14, pp. 238-300.

Kogut, T.; Slovic, P. & Västfjäll, D. (2015) “Scope insensitivity in helping decisions: Is it a matter of culture and values?”, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General , 144, pp. 1042-1052.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Why you think you’re right - even when you’re wrong #

This is a linkpost for https://www.ted.com/talks/julia_galef_why_you_think_you_re_right_even_if_you_re_wrong?language=en

What cognitive biases feel like from the inside #

This is a linkpost for https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/ERWeEA8op6s6tYCKy/what-cognitive-biases-feel-like-from-the-inside

by chaosmage

Building on the recent SSC post Why Doctors Think They’re The Best …

| What it feels like for me | How I see others who feel the same |

|---|---|

| There is controversy on the subject but there shouldn’t be because the side I am on is obviously right. | They have taken one side in a debate that is unresolved for good reason that they are struggling to understand |

| I have been studying this carefully | They preferentially seek out conforming evidence |

| The arguments for my side make obvious sense, they’re almost boring. | They’re very ready to accept any and all arguments for their side. |

| The arguments for the opposing side are contradictory, superficial, illogical or debunked. | They dismiss arguments for the opposing side at the earliest opportunity. |

| The people on the opposing side believe these arguments mostly because they are uninformed, have not thought about it enough or are being actively misled by people with bad motives. | The flawed way they perceive the opposing side makes them confused about how anyone could be on that side. They resolve that confusion by making strong assumptions that can approach conspiracy theories. |

The scientific term for this mismatch is: confirmation bias

| What it feels like for me | How I see others who feel the same |

|---|---|

| My customers/friends/relationships love me, so I am good for them, so I am probably just generally good. | They neglect the customers / friends / relationships that did not love them and have left, so they overestimate how good they are. |

| When customers / friends / relationships switch to me, they tell horror stories of who I’m replacing for them, so I’m better than those. | They don’t see the people who are happy with who they have and therefore never become their customers / friends / relationships. |

The scientific term for this mismatch is: selection bias

| What it feels like for me | How I see others who feel the same |

|---|---|

| Although I am smart and friendly, people don’t listen to me. | Although they are smart and friendly, they are hard to understand. |

| I have a deep understanding of the issue that people are too stupid or too disinterested to come to share. | They are failing to communicate their understanding, or to give unambiguous evidence if they even have it. |

| This lack of being listened to affects several areas of my life but it is particularly jarring on topics that are very important to me. | This bad communication affects all areas of their life, but on the unimportant ones they don’t even understand that others don’t understand them. |

The scientific term for this mismatch is: illusion of transparency

| What it feels like for me | How I see others who feel the same |

|---|---|

| I knew at the time this would not go as planned. | They did not predict what was going to happen. |

| The plan was bad and we should have known it was bad. | They fail to appreciate how hard prediction is, so the mistake seems more obvious to them than it was. |

| I knew it was bad, I just didn’t say it, for good reasons (e.g. out of politeness or too much trust in those who made the bad plan) or because it is not my responsibility or because nobody listens to me anyway. | In order to avoid blame for the seemingly obvious mistake, they are making up excuses. |

The scientific term for this mismatch is: hindsight bias

| What it feels like for me | How I see others who feel the same |

|---|---|

| I have a good intuition; even decisions I make based on insufficient information tend to turn out to be right. | They tend to recall their own successes and forget their own failures, leading to an inflated sense of past success. |

| I know early on how well certain projects are going to go or how well I will get along with certain people. | They make self-fulfilling prophecies that directly influence how much effort they put into a project or relationship. |

| Compared to others, I am unusually successful in my decisions. | They evaluate the decisions of others more level-headedly than their own. |

| I am therefore comfortable relying on my quick decisions. | They therefore overestimate the quality of their decisions. |

| This is more true for life decisions that are very important to me. | Yes, this is more true for life decisions that are very important to them. |

The scientific term for this mismatch is: optimism bias

Why this is better than how we usually talk about biases #

Communication in abstracts is very hard. (See: Illusion of Transparency: Why No One Understands You ) Therefore, it often fails. (See: Explainers Shoot High. Aim Low! ) It is hard to even notice communication has failed. (See: Double Illusion of Transparency ) Therefore it is hard to appreciate how rarely communication in abstracts actually succeeds.

Rationalists have noticed this. ( Example ) Scott Alexander uses a lot of concrete examples and that should be a major reason why he’s our best communicator. Eliezer’s Sequences work partly because he uses examples and even fiction to illustrate. But when the rest of us talk about rationality we still mostly talk in abstracts.

For example, this recent video was praised by many for being comparatively approachable. And it does do many things right, such as emphasize and repeat that evidence alone should not generate probabilities, but should only ever update prior probabilities. But it still spends more than half of its runtime displaying mathematical notation that no more than 3% of the population can even read. For the vast majority of people, only the example it uses can possibly “stick”. Yet the video uses its single example as no more than a means for getting to the abstract explanation.

This is a mistake. I believe a video with three to five vivid examples of how to apply Bayes’ Theorem, preferably funny or sexy ones, would leave a much more lasting impression on most people.

Our highly demanding style of communication correctly predicts that LessWrongians are, on average, much smarter, much more STEM-educated and much younger than the general population. You have to be that way to even be able to drink the Kool Aid! This makes us homogeneous, which is probably a big part of what makes LW feel tribal, which is emotionally satisfying. But it leaves most of the world with their bad decisions. We need to be Raising the Sanity Waterline and we can’t do that by continuing to communicate largely in abstracts.

The tables above show one way to do better that does the following.

- It aims low - merely to help people notice the flaws in their thinking . It will not, and does not need to, enable readers to write scientific papers on the subject.

- It reduces biases into mismatches between Inside View and Outside View. It lists concrete observations from both views and juxtaposes them.

- These observations are written in a way that is hopefully general enough for most people to find they match their own experiences.

- It trusts readers to infer from these juxtaposed observations their own understanding of the phenomena. After all, generalizing over particulars is much easier than integrating generalizations and applying them to particulars. The understanding gained this way will be imprecise, but it has the advantage of actually arriving inside the reader’s mind.

- It is nearly jargon free; it only names the biases for the benefit of that small minority who might want to learn more.

What do you think about this? Should we communicate more concretely? If so, should we do it in this way or what would you do differently?

Would you like to correct these tables? Would you like to propose more analogous observations or other biases?

Thanks to Simon, miniBill and others for helping with the draft of this post.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Purchase fuzzies and utilons separately #

This is a linkpost for https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/3p3CYauiX8oLjmwRF/purchase-fuzzies-and-utilons-separately

Someone recently cross-posted this to the main EA Facebook group, where it got a lot of attention from people who came to EA from sources other than LessWrong. I think the essay is a classic, so I’m cross-posting it to the Forum, where I expect at least a few people to see it who hadn’t seen it before.

Yesterday:

There is this very, very old puzzle/observation in economics about the lawyer who spends an hour volunteering at the soup kitchen, instead of working an extra hour and donating the money to hire someone…

If the lawyer needs to work an hour at the soup kitchen to keep himself motivated and remind himself why he’s doing what he’s doing, that’s fine. But he should also be donating some of the hours he worked at the office, because that is the power of professional specialization and it is how grownups really get things done. One might consider the check as buying the right to volunteer at the soup kitchen, or validating the time spent at the soup kitchen.

I hold open doors for little old ladies. I can’t actually remember the last time this happened literally (though I’m sure it has, sometime in the last year or so). But within the last month, say, I was out on a walk and discovered a station wagon parked in a driveway with its trunk completely open, giving full access to the car’s interior. I looked in to see if there were packages being taken out, but this was not so. I looked around to see if anyone was doing anything with the car. And finally I went up to the house and knocked, then rang the bell. And yes, the trunk had been accidentally left open.

Under other circumstances, this would be a simple act of altruism, which might signify true concern for another’s welfare, or fear of guilt for inaction, or a desire to signal trustworthiness to oneself or others, or finding altruism pleasurable. I think that these are all perfectly legitimate motives, by the way; I might give bonus points for the first, but I wouldn’t deduct any penalty points for the others. Just so long as people get helped.