What could the future hold? And why care? #

In this chapter we explore what the future might be like, and why it might matter. We’ll explore arguments for “longtermism” - the view that improving the long term future is a key moral priority. This can bolster arguments for working on reducing some of the extinction risks that we covered in the last two weeks. We’ll also explore some views on what our future could look like, and why it might be pretty different from the present.

Key concepts from this chapter include:

- Impartiality: helping those that need it the most, only discounting people according to location, time, and species if those factors are in fact morally relevant.

- Forecasting: Predicting the future is hard, but it can be worth doing in order to make our predictions more explicit and learn from our mistakes.

You will also practice the skill of calibration , with the hope that when you say that something is 60% likely, it will happen about 60% of the time. This is important for making good judgments under uncertainty.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

What We Owe the Future, Chapter 1 #

This is a linkpost for https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Rl6Zr5QIRC-yTY8iw60FPFwyzMC4IMPJ/view?usp=sharing

What We Owe The Future, by William MacAskill Chapter One

The Silent Billions #

Future people count. There could be a lot of them. We can make their lives go better.

This is the case for longtermism in a nutshell. The premises are simple, and I don’t think they’re particularly controversial. Yet taking them seriously amounts to a moral revolution—one with far-reaching implications for how activists, researchers, policy makers, and indeed all of us should think and act.

Future people count, but we rarely count them. They cannot vote or lobby or run for public office, so politicians have scant incentive to think about them. they can’t bargain or trade with us, so they have little representation in the market. And they can’t make their views heard directly: they can’t tweet, or write articles in newspapers, or march in the streets. they are utterly disenfranchised.

Previous social movements, such as those for civil rights and women’s suffrage, have often sought to give greater recognition and influence to disempowered members of society. I see longtermism as an extension of these ideals. Though we cannot give genuine political power to future people, we can at least give consideration to them. By abandoning the tyranny of the present over the future, we can act as trustees—helping to create a flourishing world for generations to come. This is of the utmost importance. Let me explain why.

Future People Count #

The idea that future people count is common sense. Future people, after all, are people. They will exist. They will have hopes and joys and pains and regrets, just like the rest of us. They just don’t exist yet.

To see how intuitive this is, suppose that, while hiking, I drop a glass bottle on the trail and it shatters. And suppose that if I don’t clean it up, later a child will cut herself badly on the shards1. In deciding whether to clean it up, does it matter when the child will cut herself? Should I care whether it’s a week, or a decade, or a century from now? No. Harm is harm, whenever it occurs.

Or suppose that a plague is going to infect a town and kill thousands. You can stop it. Before acting, do you need to know when the outbreak will occur? Does that matter, just on its own? No. The pain and death at stake are worthy of concern regardless.

The same holds for good things. Think of something you love in your own life; maybe it’s music or sports. And now imagine someone else who loves something in their life just as much. Does the value of their joy disappear if they live in the future? Suppose you can give them tickets to see their favourite band or the football team they support. To decide whether to give them, do you need to know the delivery date?

Imagine what future people would think, looking back at us debating such questions. They would see some of us arguing that future people don’t matter. But they look down at their hands; they look around at their lives. What is different? What is less real? Which side of the debate will seem more clear-headed and obvious? Which more myopic and parochial?

Distance in time is like distance in space. People matter even if they live thousands of miles away. Likewise, they matter even if they live thousands of years hence. In both cases, it’s easy to mistake distance for unreality, to treat the limits of what we can see as the limits of the world. But just as the world does not stop at our doorstep or our country’s borders, neither does it stop with our generation, or the next.

These ideas are common sense. A popular proverb says, “A society grows great when old men plant trees under whose shade they will never sit.”2 When we dispose of radioactive waste, we don’t say, “Who cares if this poisons people centuries from now?” Similarly, few of us who care about climate change or pollution do so solely for the sake of people alive today. We build museums and parks and bridges that we hope will last for generations; we invest in schools and longterm scientific projects; we preserve paintings, traditions, languages; we protect beautiful places. In many cases, we don’t draw clear lines between our concerns for the present and the future—both are in play.

Concern for future generations is common sense across diverse intellectual traditions. The Gayanashagowa , the centuries-old oral constitution of the Iroquois Confederacy, has a particularly clear statement. It exhorts the Lords of the Confederacy to “have always in view not only the present but also the coming generations.”3 Oren Lyons, a faithkeeper for the Onondaga and Seneca nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, phrases this in terms of a “seventh-generation” principle, saying, “We . . . make every decision that we make relate to the welfare and well-being of the seventh generation to come. . . . We consider: will this be to the benefit of the seventh generation?”4

However, even if you grant that future people count, there’s still a question of how much weight to give their interests. Are there reasons to care more about people alive today?

Two reasons stand out to me. The first is partiality. We often have stronger special relationships with people in the present, like family, friends, and fellow citizens, than with people in the future. It’s common sense that you can and should give extra weight to your near and dear.

The second reason is reciprocity. Unless you live as a recluse in the wilderness, the actions of an enormous number of people—teachers, shop- keepers, engineers, and indeed all taxpayers—directly benefit you and have done so throughout your life. We typically think that if someone has benefited you, that gives you a reason to repay them. But future people don’t benefit you the way others in your generation do.5

Special relationships and reciprocity are important. But they do not change the upshot of my argument. I’m not claiming that the interests of present and future people should always and everywhere be given equal weight. I’m just claiming that future people matter significantly. Just as car- ing more about our children doesn’t mean ignoring the interests of strangers, caring more about our contemporaries doesn’t mean ignoring the interests of our descendants.

To illustrate, suppose that one day we discover Atlantis, a vast civilisation at the bottom of the sea. We realise that many of our activities affect Atlantis. When we dump waste into the oceans, we poison its citizens; when a ship sinks, they recycle it for scrap metal and other parts. We would have no special relationships with the Atlanteans, nor would we owe them repayment for benefits they had bestowed on us. But we should still give serious consideration to how our actions affect them.

The future is like Atlantis. It, too, is a vast, undiscovered country6; and whether that country thrives or falters depends, in significant part, on what we do today.

The Future Is Big #

It’s common sense that future people count. So, too, is the idea that, morally, the numbers matter. If you can save one person or ten from dying in a fire, then, all else being equal, you should save ten; if you can cure a hundred people or a thousand of a disease, you should cure a thousand. This matters, because the number of future people could be huge.

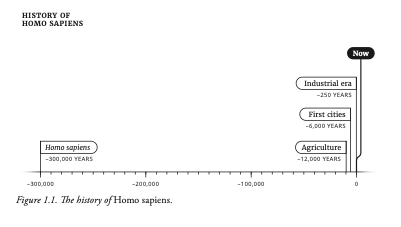

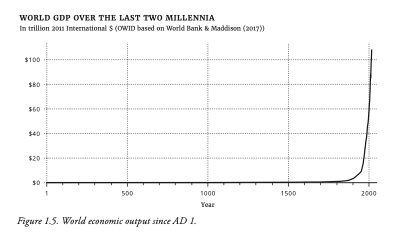

To see this, consider the long-run history of humanity. There have been members of the genus Homo on Earth for over 2.5 million years7. Our species, Homo sapiens , evolved around three hundred thousand years ago. Agri- culture started just twelve thousand years ago, the first cities formed only six thousand years ago, the industrial era began around 250 years ago, and all the changes that have happened since then—transitioning from horse-drawn carts to space travel, leeches to heart transplants, mechanical calculators to supercomputers—occurred over the course of just three human lifetimes8.

How long will our species last? Of course, we don’t know. But we can make informative estimates that take our uncertainty into account, including our uncertainty about whether we’ll cause our own demise.

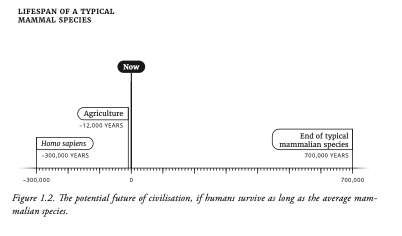

To illustrate the potential scale of the future, suppose that we only last as long as the typical mammalian species—that is, around one million years9. Also assume that our population continues at its current size. In that case, there would be eighty trillion people yet to come; future people would out- number us ten thousand to one.

Of course, we must consider the whole range of ways the future could go. Our life span as a species could be much shorter than that of other mammals if we cause our own extinction. But it could also be much longer. Un- like other mammals, we have sophisticated tools that help us adapt to varied environments; abstract reasoning, which allows us to make complex, long- term plans in response to novel circumstances; and a shared culture that allows us to function in groups of millions. These help us avoid threats of extinction that other mammals can’t10.

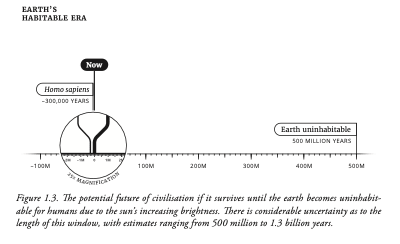

This has an asymmetric impact on humanity’s life expectancy. The future of civilisation could be very short, ending within a few centuries. But it could also be extremely long. The earth will remain habitable for hundreds of millions of years. If we survive that long, with the same population per century as now, there will be a million future people for every person alive today. And if humanity ultimately takes to the stars, the timescales become literally astronomical. The sun will keep burning for five billion years; the last conventional star formations will occur in over a trillion years; and, due to a small but steady stream of collisions between brown dwarfs, a few stars will still shine a million trillion years from now11.

The real possibility that civilisation will last such a long time gives humanity an enormous life expectancy. A 10 percent chance of surviving five hundred million years until the earth is no longer habitable gives us a life expectancy of over fifty million years; a 1 percent chance of surviving until the last conventional star formations give us a life expectancy of over ten billion years12.

Ultimately, we shouldn’t care just about humanity’s life expectancy but also about how many people there will be. So we must ask: How many people in the future will be alive at any one time?

Future populations might be much smaller or much larger than they are today. But if the future population is smaller, it can be smaller by eight billion at most—the size of today’s population. In contrast, if the future population is bigger, it could be much bigger. The current global population is already over a thousand times larger than it was in the hunter-gatherer era. If global population density increased to that of the Netherlands—an agricultural net exporter—there would be seventy billion people alive at any one time.13 This might seem fantastical, but a global population of eight billion would have seemed fantastical to a prehistoric hunter-gatherer or an early agriculturalist.

Population size could get dramatically larger again if we one day take to the stars. Our sun produces billions of times as much sunlight as lands on Earth, there are tens of billions of other stars across our galaxy, and billions of galaxies are accessible to us14. There might therefore be vastly more people in the distant future than there are today.

Just how many? Precise estimates are neither possible nor necessary. On any reasonable accounting, the number is immense.

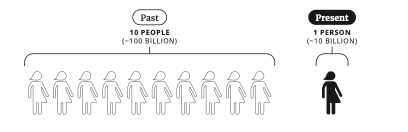

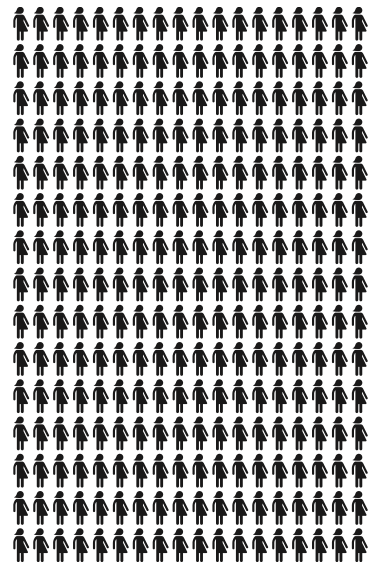

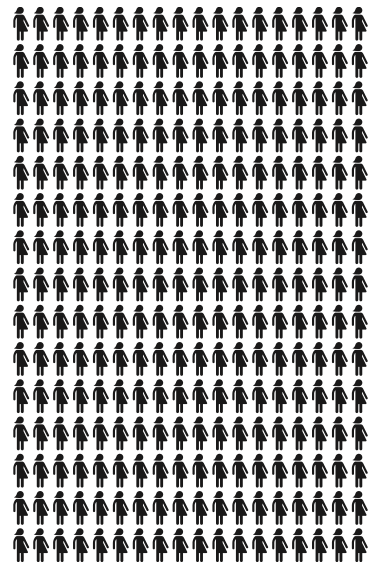

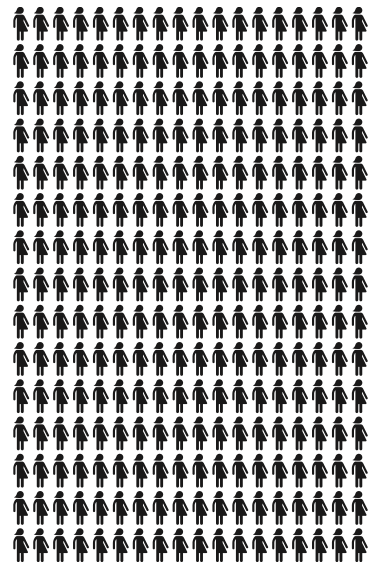

To see this, look at the following diagram. Each figure represents ten billion people. So far, roughly one hundred billion people have ever lived. These past people are represented as ten figures. The present generation consists of almost eight billion people, which I’ll round up to ten billion and represent with a single figure:

Next, we’ll represent the future. Let’s just consider the scenario where we stay at current population levels and live on Earth for five hundred million years. These are all the future people:

Represented visually, we begin to see how many lives are at stake. But I cut the diagram short. The full version would fill twenty thousand pages— saturating this book a hundred times over. Each figure would represent ten billion lives, and each of those lives could be flourishing or wretched.

Earlier, I suggested that humanity today is like an imprudent teenager: most of our life is ahead of us, and decisions that impact the rest of that life are of colossal importance. But, really, this analogy understates my case. A teenager knows approximately how long she can expect to live. But we do not know humanity’s life expectancy. We are more like a teenager who, for all she knows, might accidentally cause her own death in the next few months but also might live for a thousand years. If you were in such a situation, would you think seriously about the long life that might be ahead of you, or would you ignore it?

The sheer size of the future can be dizzying. Typically, “longterm” think- ing involves attention to years or decades at most. But even with a low estimate of humanity’s life expectancy, this is like a teenager believing that longterm thinking means considering tomorrow but not the day after.

Despite how overwhelming thoughts of our future can be, if we truly care about the interests of future generations—if we recognize that they are real people, capable of happiness and suffering just like us—then we have a duty to consider how we might impact the world they inhabit.

The Value of the Future #

The future could be very big. It could also be very good—or very bad.

To get a sense of how good, we can look at some of the progress humanity has made over the last few centuries. Two hundred years ago, average life expectancy was less than thirty; today, it is seventy-three15. Back then, over 80 percent of the world lived in extreme poverty; now, less than 10 percent does16. Back then, only about 10 percent of adults could read; today, more than 85 percent can.17

Collectively we have the power both to encourage these positive trends and to change course on the negative trends, like the dramatic increases in carbon dioxide emissions and in the number of animals suffering in factory farms. We can build a world where everyone lives like the happiest people in the most well-off countries today, a world where no one lives in poverty, no one lacks adequate medical care, and, insofar as is possible, everyone is free to live as they want.

But we could do even better still—far better. The best that we have seen so far is a poor guide to what is possible. To get some inkling of this, consider the life of a rich man in Britain in 1700—a man with access to the best food, health care, and luxuries available at the time. For all his advantages, such a man could easily die of smallpox, syphilis, or typhus. If he needed surgery or had a toothache, the treatment would be agonising and carry a significant risk of infection. If he lived in London, the air he breathed would be seventeen times as polluted as it is today18. Travelling even within Britain could take weeks, and most of the globe was entirely inaccessible to him. If he had imagined a future merely where most people were as rich as him, he would have failed to anticipate many of the things that improve our lives, like electricity, anaesthesia, antibiotics, and mod- ern travel.

It’s not just technology that has improved people’s lives; moral change has done so, too. In 1700, women were unable to attend university, and the feminist movement did not exist.19 If that well-off Brit was gay, he could not love openly; sodomy was punishable by death.20 In the late 1700s, three in four people globally were the victims of some form of forced labour; now less than 1 percent are.21 In 1700, no one lived in a democracy. Now over half the world does.22

Much of the progress we’ve made since 1700 would have been very difficult for people back then to anticipate. And that’s with only a three-century gap. Humanity could last for millions of centuries on Earth alone. On such a scale, if we anchor our sense of humanity’s potential to a fixed-up version of our present world, we risk dramatically underestimating just how good life in the future could be.

Consider the very best moments in your life—moments of joy, beauty, and energy, like falling in love, or achieving a lifelong goal, or having some creative insight. These moments provide proof of what is possible: we know that life can be at least as good as it is then. But they also show us a direction in which our lives can move, leading somewhere we have yet to go. If my best days can be hundreds of times better than my typically pleasant but humdrum life, then perhaps the best days of those in the future can be hundreds of times better again.

I’m not claiming that a wonderful future is likely. Etymologically, “utopia” means “no-place,” and indeed the path from here to some ideal future state is very fragile. But a wonderful future is not just a fantasy, either. A better word would be “eutopia,” meaning “good place”—something to strive for. It’s a future that, with enough patience and wisdom, our descendants could actually build—if we pave the way for them.

And though the future could be wonderful, it could also be terrible. To see this, look at some of the negative trends of the past and imagine a future where they are the dominant forces guiding the world. Consider that slavery had all but disappeared from France and England by the end of the twelfth century, but in the colonial era those same countries became slave traders on a massive scale.23 Or consider that the mid-twentieth century saw totalitarian regimes emerging even out of democracies. Or that we used scientific advances to build nuclear weapons and factory farms.

Just as eutopia is a real possibility, so is dystopia. The future could be one where a single totalitarian regime controls the world, or where today’s qual- ity of life is but a distant memory of a former Golden Age, or where a third world war has led to the complete destruction of civilisation. Whether the future is wonderful or terrible is, in part, up to us.

Not Just Climate Change #

Even if you accept that the future is big and important, you might be skeptical that we can positively affect it. And I agree that working out the long- run effects of our actions is very hard. There are many considerations at play, and our understanding of them is just beginning. My aim with this book is to stimulate further work in this area, not to be definitive in any conclusions about what we should do. But the future is so important that we’ve got to at least try to figure out how to steer it in a positive direction. And, already, there are some things we can say.

Looking to the past, though there are not many examples of people deliberately aiming at long-run impacts, they do exist, and some had surprising levels of success. Poets provide one source. In Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 (“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”) the author notes that through his art he can preserve the young man he admires for all eternity:24

But thy eternal summer shall not fade, > …………………

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st. > So long as men can breathe or eyes can see. > So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.25

Sonnet 18 was written in the 1590s but echoes a tradition that goes back much further26. In 23 BC the Roman poet Horace began the final poem in his Odes with these lines:27

I have finished a monument more lasting than bronze, more lofty than the regal structure of the pyramids, one which neither corroding rain nor the un- governable North Wind can ever destroy, nor the countless series of the years, nor the flight of time.

I shall not wholly die, and a large part of me will elude the Goddess of Death. 28

These claims seem bombastic, to say the least. But, plausibly, these poets’ attempts at immortality succeeded. They have survived many hundreds of years and are in fact flourishing as the years pass: more people read Shakespeare today than did in his own time, and the same is probably true of Horace. And as long as some member of each future generation is willing to pay the tiny cost involved in preserving or replicating some representation of these poems, they will persist forever.

Other writers have also successfully aimed at very longterm impact. Thucydides wrote his History of the Peloponnesian War in the fifth century BC.29 Many consider him the first Western historian to try to depict events faithfully and analyse their causes.30 He believed he was describing general truths, and he deliberately wrote his history so that it could be influential far into the future:

It will be enough for me, however, if these words of mine are judged useful by those who want to understand clearly the events which happened in the past and which (human nature being what it is) will, at some time or other and in much the same ways, be repeated in the future. My work is not a piece of writing designed to meet the taste of an immediate public, but was done to last for ever.31

Thucydides’s work is still enormously influential to this day. It is required reading at the West Point and Annapolis military academies and the US Naval War College.32 The widely read 2017 book Destined for War , by political scientist Graham Allison, had the subtitle Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? Allison analyses US-China relations in the same terms that Thucydides used for Sparta and Athens. As far as I know, Thucydides is the first person in recorded history to have deliberately aimed at longterm impact and succeeded.

More recent examples come from the United States’ Founding Fathers. The US Constitution is almost 250 years old and has mostly remained the same throughout its life. Its founding was of enormous longterm importance, and many of the Founding Fathers were well aware of this. John Adams, the second president of the United States, commented, “The institutions now made in America will not wholly wear out for thousands of years. It is of the last importance, then, that they should begin right. If they set out wrong, they will never be able to return, unless it be by accident, to the right path.”33

Similarly, Benjamin Franklin had such a reputation for believing in the health and longevity of the United States that in 1784 a French mathematician wrote a friendly satire of him, suggesting that if Franklin was sin- cere in his beliefs, he should invest his money to pay out on social projects centuries later, getting the benefits of compound interest along the way.34 Franklin thought it was a great idea, and in 1790 he invested £1000 (about $135,000 in today’s money) each for the cities of Boston and Philadelphia: three-quarters of the funds would be paid out after one hundred years, and the remainder after two hundred years. By 1990, when the final funds were distributed, the donation had grown to almost $5 million for Boston and $2.3 million for Philadelphia.35

The Founding Fathers themselves were influenced by ideas developed almost two thousand years before them. Their views on the separation of powers were foreshadowed by Locke and Montesquieu, who drew on Polybius’s analysis of Roman governance from the second century BC.36 We also know that several Founding Fathers were familiar with Polybius’s work themselves.37

Those of us in the present don’t need to be as influential as Thucydides or Franklin to predictably impact the longterm future. In fact, we do it all the time. We drive. We fly. We thereby emit greenhouse gases with very long-lasting effects. Natural processes will return carbon dioxide concentrations to preindustrial levels only after hundreds of thousands of years.38 These are timescales usually associated with radioactive nuclear waste.39 However, with nuclear power we carefully store and plan to bury the waste products; with fossil fuels we belch them into the air.40

In some cases, the geophysical impacts of this warming get even more extreme over time rather than “washing out.”41 The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects that in the medium-low-emissions scenario, which is now widely seen to be the most likely, sea level would rise by around 0.75 metres by the end of the century.42 But it would keep rising well past the year 2100. After ten thousand years, sea level would be ten to twenty metres higher than it is today.43 Hanoi, Shanghai, Kolkata, Tokyo, and New York would all be mostly below sea level.44

Climate change shows how actions today can have longterm consequences. But it also highlights that longterm-oriented actions needn’t involve ignoring the interests of those alive today. We can positively steer the future while improving the present, too.

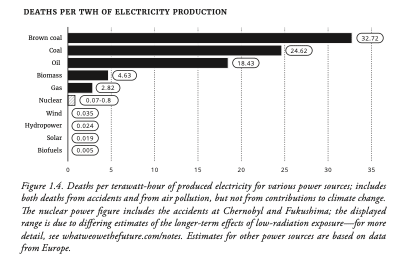

Moving to clean energy has enormous benefits in terms of present-day human health. Burning fossil fuels pollutes the air with small particles that cause lung cancer, heart disease, and respiratory infections.45 As a result, every year about 3.6 million people die prematurely.46 Even in the European Union, which in global terms is comparatively unpolluted, air pollution from fossil fuels causes the average citizen to lose a whole year of life.47

Decarbonisation—that is, replacing fossil fuels with cleaner sources of energy—therefore has large and immediate health benefits in addition to the longterm climate benefits. Once one accounts for air pollution, rapidly decarbonising the world economy is justified by the health benefits alone.48

Decarbonisation is therefore a win-win, improving life in both the long and the short term. In fact, promoting innovation in clean energy—such as solar, wind, next-generation nuclear, and alternative fuels—is a win on other fronts, too. By making energy cheaper, clean energy innovation improves living standards in poorer countries. By helping keep fossil fuels in the ground, it guards against the risk of unrecovered collapse that I’ll discuss in Chapter 6. By furthering technological progress, it reduces the risk of longterm stagnation that I’ll discuss in Chapter 7. A win-win-win-win-win.

Decarbonisation is a proof of concept for longtermism. Clean energy in- novation is so robustly good, and there is so much still to do in that area that I see it as a baseline longtermist activity against which other potential actions can be compared. It sets a high bar.

But it’s not the only way of affecting the long term. The rest of this book tries to give a systematic treatment of the ways in which we can positively influence the longterm future, suggesting that moral change, wisely govern- ing the ascent of artificial intelligence, preventing engineered pandemics, and averting technological stagnation are all at least as important, and often radically more neglected.

Our Moment in History #

The idea that we could affect the longterm future, and that there could be so much at stake, might just seem too wild to be true. This is how things initially seemed to me.49

But I think that the wildness of longtermism comes not from the moral premises that underlie it but from the fact that we live at such an unusual time.50

We live in an era that involves an extraordinary amount of change. To see this, consider the rate of global economic growth, which in recent decades averaged around 3 percent per year.51 This is historically unprecedented. For the first 290,000 years of humanity’s existence, global growth was close to 0 percent per year; in the agricultural era that increased to around 0.1 percent, and it accelerated from there after the Industrial Revolution. It’s only in the last hundred years that the world economy has grown at a rate above 2 per- cent per year. Putting this another way: from 10,000 BC onwards, it took many hundreds of years for the world economy to double in size. The most recent doubling took just nineteen years.52 And it’s not just that rates of economic growth are historically unusual; the same is true for rates of energy use, carbon dioxide emissions, land use change, scientific advancement, and arguably moral change, too.53

So we know that the present era is extremely unusual compared to the past. But it’s also unusual compared to the future. This rapid rate of change cannot continue forever, even if we entirely decouple growth from carbon emissions and even if in the future we spread to the stars. To see this, suppose that future growth slows a little to just 2 percent per year.54 At such a rate, in ten thousand years the world economy would be 10⁸⁶ times larger than it is today—that is, we would produce one hundred trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion times as much output as we do now. But there are less than 10⁶⁷ atoms within ten thousand light years of Earth.55 So if current growth rates continued for just ten millennia more, there would have to be ten million trillion times as much output as our current world produces for every atom that we could, in principle, access. Though of course we can’t be certain, this just doesn’t seem possible.56

Humanity might last for millions or even billions of years to come. But the rate of change of the modern world can only continue for thousands of years. What this means is that we are living through an extraordinary chapter in humanity’s story. Compared to both the past and the future, every decade we live through sees an extremely unusual number of economic and technological changes. And some of these changes—like the inventions of fossil fuel power, nuclear weapons, engineered pathogens, and advanced artificial intelligence—have the potential to impact the whole course of the future.

It’s not only the rapid rate of change that makes this time unusual. We’re also unusually connected.57 For over fifty thousand years, we were broken up into distinct groups; there was simply no way for people across Africa, Europe, Asia, or Australia to communicate with one another.58 Between 100 BC and AD 150 the Roman Empire and the Han dynasty each comprised up to 30 percent of the world’s population, yet they barely knew of each other.59 Even within one empire, one person had very limited ability to communicate with someone far away.60

In the future, if we spread to the stars, we will again be separated. The galaxy is like an archipelago, vast expanses of emptiness dotted with tiny pinpricks of warmth. If the Milky Way were the size of Earth, our solar system would be ten centimetres across and hundreds of metres would separate us from our neighbours. Between one end of the galaxy and the other, the fastest possible communication would take a hundred thousand years; even between us and our closest neighbour, there-and-back communication would take almost nine years.

In fact, if humanity spreads far enough and survives for long enough, it will eventually become impossible for one part of civilisation to communicate with another. The universe is composed of millions of groups of galaxies.61 Our own is called, simply, the Local Group. The galaxies within each group are close enough to each other that gravity binds them together forever.62 But, because the universe is expanding, the groups of galaxies will eventually be torn apart from each other. Over 150 billion years in the future, not even light will be able to travel from one group to another.63

The fact that our time is so unusual gives us an outsized opportunity to make a difference. Few people who ever live will have as much power to positively influence the future as we do. Such rapid technological, social, and environmental change means that we have more opportunity to affect when and how the most important of these changes occur, including by managing technologies that could lock in bad values or imperil our survival. Civilisation’s current unification means that small groups have the power to influence the whole of it. New ideas are not confined to a single continent, and they can spread around the world in minutes rather than centuries.

The fact that these changes are so recent means, moreover, that we are out of equilibrium: society has not yet settled down into a stable state, and we are able to influence which stable state we end up in. Imagine a giant ball rolling rapidly over a rugged landscape. Over time it will lose momentum and slow, settling at the bottom of some valley or chasm. Civilisation is like this ball: while still in motion, a small push can affect in which direction we roll and where we come to rest.

Why I find longtermism hard, and what keeps me motivated #

[Cross-posted from the 80,000 Hours blog ]

I find working on longtermist causes to be — emotionally speaking — hard: There are so many terrible problems in the world right now. How can we turn away from the suffering happening all around us in order to prioritise something as abstract as helping make the long-run future go well?

A lot of people who aim to put longtermist ideas into practice seem to struggle with this, including many of the people I’ve worked with over the years. And I myself am no exception — the pull of suffering happening now is hard to escape. For this reason, I wanted to share a few thoughts on how I approach this challenge, and how I maintain the motivation to work on speculative interventions despite finding that difficult in many ways.

This issue is one aspect of a broader issue in EA: figuring out how to motivate ourselves to do important work even when it doesn’t feel emotionally compelling. It’s useful to have a clear understanding of our emotions in order to distinguish between feelings and beliefs we endorse and those that we wouldn’t — on reflection — want to act on.

What I’ve found hard #

First, I don’t want to claim that everyone finds it difficult to work on longtermist causes for the same reasons that I do, or in the same ways. I’d also like to be clear that I’m not speaking for 80,000 Hours as an organisation.

My struggles with the work I’m not doing tend to centre around the humans suffering from preventable diseases in poor countries. That’s largely to do with what I initially worked on when I came across effective altruism. For other people, it’s more salient that they aren’t actively working to prevent the barbarity of some factory farming practices. I’m not going to talk about all of the ways in which people might find it hard to focus on the long-run future — for the purposes of this article, I’m going to focus specifically on my own experience.

I feel a strong pull to help people now #

A large part of the suffering in the world today simply shouldn’t exist. People are suffering and dying for want of cheap preventative measures and cures. Diseases that rich countries have managed to totally eradicate still plague millions around the world. There’s strong evidence for the efficacy of cheap interventions like insecticide-treated anti-malaria bed nets. Yet many of us in rich countries are well off financially, and spend a significant proportion of our income on non-necessity goods and services. In the face of this absurd and preventable inequity, it feels very difficult to believe that I shouldn’t be doing anything to ameliorate it.

Likewise, it often feels hard to believe that I shouldn’t be helping people geographically close to me — such as homeless people in my town, or people who are being illegitimately incarcerated in my country. It’s hard to deal with there being visible and preventable suffering that I’m not doing anything to combat.

For me, putting off helping people alive today in favour of helping those in the future is even harder than putting off helping those in my country in favour of those on the other side of the world. This is in part due to the sense that if we don’t take actions to improve the future, there are others coming after us who can. By contrast, if we don’t take action to help today’s global poor, those coming after us cannot step in and take our place. The lives we fail to save this year are certain to be lost and grieved for.

Another reason this is challenging is that wealth seems to be sharply increasing over time. This means that we have every reason to believe that people in the future will be far richer than people today, and it would seem to follow that people in the future don’t need our help as much as those in the present. There is no analogue in the case of helping people far away geographically.

The arguments for longtermism aren’t emotionally compelling to me #

The reasons we have for improving the lives of those currently alive are emotionally gripping. That’s in part because these are clearly important duties weighing on us, whose force can be vitiated only by some even stronger duty. By comparison, the case for focusing on the longer term feels far more speculative, and relies on careful weighing of complex arguments.

Below I sketch out how I see the arguments for longtermism, and why — despite being convinced of them intellectually — they don’t diminish my sense that we should be alleviating present suffering instead. I’d like to note that this isn’t intended to be a rigorous statement of why we should focus on longtermist causes (which 80,000 Hours has written about elsewhere ).

The future of sentient beings is potentially unimaginably large. That means if we have only a very small chance of affecting it in a lasting and positive way, taking that chance is worth it.

One way in which we could affect the long run is by preventing the extinction of all life. The fact that present people could potentially wipe out everyone to come means it isn’t true that the people who come after us will have the chance to improve the future if we don’t. It also makes irrelevant the fact that people in the future could be richer than us.

There may also be ways that the value in the future can be irreversibly curtailed due to the lock-in of a totalitarian regime rather than an extinction event. That suggests future people may well exist, but be very badly off without our intervention.

These terrible outcomes do seem possible to me. They seem to be the kinds of risks we should be investigating, to figure out whether we can reduce them. And in fact there are many reasons to think that society is usually bad at handling these types of risks: Businesses have incentives to make money in the short run, politicians want to get re-elected in the next couple of years, and individuals tend to be bad at planning (even for their own futures!).

The arguments above make sense to me and I believe them. I believe I ought to prioritise working on improving the long-run future.

Despite this, the arguments still feel speculative. And even if they’re right, there’s no guarantee that I’ll actually have any impact by e.g. improving the representation of future generations in our legislation, or by increasing the body of good global priorities research — let alone by simply trying to do either one of those. I just have to place a bet on being able to make a big positive difference, even though I know it might not work. That makes choosing to do these things — rather than e.g. donate to bednet distribution — feel uncomfortably like gambling with the lives of others.

How I handle that difficulty #

Given these problems, it sometimes feels hard to be motivated to do what I think I ought to. One thing I’m heartened by is that working on the long run feels hard in precisely the way I think we should expect effective altruism to feel hard: The more salient a particular problem is — and the more compelling working on it seems — the more we should expect it to already have people tackling it. So I should expect working on the most pressing problems not to feel as intuitively urgent and important as working on some other problems. If it did, it would be less neglected.

What makes the most difference in my motivation day to day is being part of a team I deeply respect and care about. My drive to make those around me happy and to not let down my colleagues makes it easy to work hard. They don’t necessarily need to share my values — if I were earning to give, and needed to do my job well in order to maintain (and increase!) my income, I expect it would very much help me to have colleagues who cared about working to a high standard and the success of the company. In order to avoid letting them down, I imagine I’d be motivated to work hard and do my part.

Another thing which makes a significant difference to my motivation is continuing to think and talk about arguments around what causes and interventions are most pressing. One way I do this is to articulate intuitive worries I have that I’m not working on the right thing as they come up, and debate them with people who have similar values to me. Doing that helps me to get a sense for which of my views feel intuitive but I don’t ultimately believe, and which I actually endorse and can defend.

I also try to keep reading and engaging with arguments that indicate that I should work on other problems. It’s particularly important to keep questioning and fleshing out counterintuitive beliefs, because you can’t rely on your gut to tell you when you’re getting carried away (it already thinks you’re off course!).

That said, it would be disorienting and demotivating to be continuously questioning your direction or work. An important time to do this might be when you’re about to engage on a new project, or change direction significantly. (Although I also quite enjoy keeping track of interesting new arguments as they come up, for example on the EA forum.)

For me, it has also been helpful to make concrete commitments to do what’s most effective. I’m a member of Giving What We Can , which means I’ve pledged to give 10% of my income to the organisations I believe can most effectively improve the world. I actually tend to donate a bit on top of my pledge each year — some to an animal welfare organisation to offset eating meat, and some to a global development organisation (typically the Against Malaria Foundation) because I hate the idea of not doing anything to reduce global poverty. But I always give my 10% to the organisations that I think on balance will do the most good in expectation, because I promised I would.

A technique I have more mixed feelings about is making the harms or lack of benefits in the future feel more concrete. For example, I might imagine that humanity is extinguished in a man-made pandemic as a result of reckless biowarfare, and that the accessible universe then remains empty of intelligent life for eons. Thinking about examples like this give my intuitions something to latch onto, and remind me that future harms will be no less real to those experiencing them than present harms.

One of my reservations with this approach is that because there are so many possible terrible outcomes for the world, it seems potentially misleading to latch on to any specific one. Doing so might affect your actions in ways you didn’t intend. One possible way to avoid that might be to try to picture a concrete positive outcome: Set your sights on a world of flourishing beings spread across the universe. Personally, I tend to find that less motivating, in part because I think that as we’re currently constituted, living beings have a far greater capacity for pain than pleasure.

With all the above techniques, I think it really helps to have others around you who are thinking in similar ways — you can share concrete suggestions about what works, and feel the relief of knowing you’re not the only one finding things hard. Being part of the effective altruism community makes a big difference for me in these ways, whether that’s online (for example, the EA Forum) or in person (I’ve been lucky enough to usually live somewhere with a thriving local EA group).

When I’m really struggling to do the right thing, I come back to the fact that with all the uncertainty around longtermism, there is one thing I’m sure about: I care about people in the future, just like I care about people now. I would send a bednet to protect a baby, even if the baby wasn’t yet conceived, and I would train a paediatrician now for the benefit of children for decades to come.

There are so many possible people in the future who have no ability at all to advocate for themselves. Society as it stands is essentially entirely ignoring them. I can’t see those people in pictures, and I have no idea which things will actually afflict them, or if they’ll ever get to live. But I can use my career to try to make things better for them, in expectation. And I believe that’s what I should do.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Why I am probably not a longtermist #

tl;dr: I am much more interested in making the future good, as opposed to long or big, as I neither think the world is great now nor am convinced it will be in the future. I am uncertain whether there are any scenarios which lock us into a world at least as bad as now that we can avoid or shape in the near future. If there are none, I think it is better to focus on “traditional neartermist” ways to improve the world.

I thought it might be interesting to other EAs why I do not feel very on board with longtermism, as longtermism is important to a lot of people in the community.

This post is about the worldview called longtermism . It does not describe a position on cause prioritisation. It is very possible for causes commonly associated with longtermism to be relevant under non-longtermist considerations.

I structured this post by crux and highlighted what kind of evidence or arguments would convince me that I am wrong, though I am keen to hear about others which I might have missed! I usually did not investigate my cruxes thoroughly. Hence, only ‘probably’ not a longtermist.

The quality of the long-term future #

1. I find many aspects of utilitarianism uncompelling. #

You do not need to be a utilitarian to be a longtermist. But I think depending on how and where you differ from total utiliarianism, you will probably not go ‘all the way’ to longtermism.

I very much care about handing the world off in a good state to future generations. I also care about people’s wellbeing regardless of when it happens. What I value less than a total utilitarian is bringing happy people into existence who would not have existed otherwise. This means I am not too fussed about humanity’s failure to become much bigger and spread to the stars. While creating happy people is valuable, I view it as much less valuable than making sure people are not in misery. Therefore I am not extremely concerned about the lost potential from extinction risks (but I very much care about its short-term impact), although that depends on how good and long I expect the future to be (see below).

What would convince me otherwise:

I not only care about pursuing my own values, but I would like to ensure that other people’s reflected values are implemented. For example, if it turned out that most people in the world really care about increasing the human population in the long term, I would prioritise it much more. However I am a bit less interested in the sum of individual preferences, but more the preferences of a wide variety of groups. This is to give more weight to rarer worldviews as well as not rewarding one group outbreeding the other or spreading their values in an imperialist fashion.

I also want to give the values of people who are suffering the most more weight. If they think the long-term future is worth prioritising over their current pain, I would take this very seriously.

Alternatively, convincing me of moral realism and the correctness of utilitarianism within that framework would also work. So far I have not seen a plain language explanation of why moral realism makes any sense, but it would probably be a good start.

If the world suddenly drastically improved and everyone had as good a quality of life as my current self, I would be happy to focus on making the future big and long instead of improving people’s lives.

2. I do not think humanity is inherently super awesome. #

A recurring theme in a lot of longtermist worldviews seems to be that humanity is wonderful and should therefore exist for a long time. I do not consider myself a misanthrope, I expect my views to be average for Europeans. Humanity has many great aspects which I like to see thrive.

But I find the overt enthusiasm for humanity most longtermists seem to have confusing. Even now, humanity is committing genocides, letting millions of people die of hunger, enslaving and torturing people as well as billions of factory-farmed animals. I find this hard to reconcile with a “humanity is awesome” worldview.

A common counterargument to this seems to be that these are problems, but we have just not gotten around to fixing them yet. That humans are lazy, not evil. This does not compel me. I not only care about people living good lives, I also care about them being good people. Laziness is no excuse.

Right now, we have the capacity to do more. Mostly, we do not. Few people who hear about GiveWell recommended charities decide to donate a significant amount of their income. People go on tourist intercontinental flights despite knowing about climate change. Many eat meat despite having heard of conditions on factory farms. Global aid is a tiny proportion of most developed countries’ budgets. These examples are fairly cosmopolitan, but I do not consider this critical.

Taken one at a time, you can quibble with these examples. Sometimes people actually lack the information. They can have empirical disagreements or different moral views (e.g. not considering animals to be sentient). Sometimes they triage and prioritise other ways of doing good. I am okay with all of these reasons.

But in the end, it seems to me that many people have plenty of resources to do better and yet there are still enormous problems left. It is certainly great if we set up better systems in the future to reduce misery and have the right carrots and sticks in place to get people to behave better. But I am unenthusiastic about a humanity which requires these to behave well.

This also makes me reluctant to put a lot of weight on helping people being good regardless of when it happens. This is only true if people in the future are as morally deserving as people are today.

Or putting this differently: if humans really were so great, we would not need to worry about all these risks to the future. They would solve themselves.

What would convince me otherwise:

I would be absolutely thrilled to be wrong about how moral people are where I live! Admittedly, I find it hard to think of plausible evidence as it seems to be in direct contradiction to the world I observe. Maybe it is genuinely a lack of information that stops people from acting better, as e.g. Max Roser from Our World in Data seems to believe. Information campaigns having large effects would be persuasive.

I am unfamiliar with how seriously people take their moral obligations in other places and times. Maybe the lack of investment I see is a local aberration.

Even though this should not have an impact on my worldview, I would probably also feel more comfortable with the longtermist idea if I saw a stronger focus on social or medical engineering to produce (morally) better people within the longtermist community.

3. I am unsure whether the future will be better than today. #

In many ways, the world has gotten a lot better. Extreme poverty is down and life expectancy is up. Fewer people are enslaved. I am optimistic about these positive trends continuing.

What I feel more skeptical of is how much of the story these trends tell. While probably most people agree that having fewer people starve and die young is good, there are plenty of trends which get lauded by longtermists which others might feel differently about, for example the decline in religiosity. Or they can put weight on different aspects. Someone who values animals in factory farms highly might not think the world has improved.

I am concerned that seeing the world as improving is dependent on a worldview with pretty uncommon values. Using the lens of Haidt’s moral foundations theory it seems that most of the improvements are in the Care/harm foundation, while the world may not have improved according to other moral foundations like Loyalty/betrayal or Sanctity/degradation.

Also, many world improvements I expect to peter out before they become negative. But I am worried that some will not. For example, I think increased hedonism and individualism have both been a good force, but if overdone I would consider them to make the world worse, and it seems to me we are either almost or already there.

I am generally concerned about trends to overshoot their original good aim by narrowly optimising too much. Optimising for profit is the clearest example. I wrote a bit more about this here .

If the world is not better than it was in the past, extrapolating towards expecting an even better future does not work. For me this is another argument on wanting to focus on making the future good instead of long or big.

On a related note, while this is not an argument which deters me from longtermism, some longtermists looking forward to futures which I consider to be worthless (e.g. the hedonium shockwave) puts me off. Culturally many longtermists seem to favour more hedonism, individualism and techno-utopianism than I would like.

What would convince me otherwise:

I am well aware lots of people are pessimistic about the future because they get simple facts about how the world has been changing wrong. Yet I am interested in learning more about how different worldviews lead to perceiving the world as improving or not.

The length of the long-term future #

I do not feel compelled by arguments that the future could be very long. I do not see how this is possible without at least soft totalitarianism, which brings its own risks of reducing the value of the future.

Or looking at it differently, people working on existential risks spent some years convincing me that existentials risks are pretty big. Switching from that argument to work on existential risks to longtermism, which requires reaching existential security, gives me a sense of whiplash.

See also this shortform post on the topic. One argument brought up there is the Lindy rule, pointing out that self-propagating systems have existed for billions of years so we can expect this length again. But I do not see why self-propagating systems should be the baseline, I am only interested in applying the Lindy rule to a morally worthwhile human civilisation which has been rather short in comparison.

I am also not keen to base decisions on rough expected value calculations in which the assessment of the small probability is uncertain and the expected value is the primary argument (as opposed to a more ‘cluster thinking’ based approach). I am not in principle opposed to such decisions, but my own track record with such decisions is very poor. : the predicted expected value from back of the envelope calculations does not materialise.

I also have traditional Pascal’s mugging type concerns for prioritizing the potentially small probability of a very large civilisation.

What would convince me otherwise:

I would appreciate solid arguments on how humanity could reach existential security.

The ability to influence the long-term future #

I am unconvinced that people can reliably have a positive impact which dissipates further into the future than 100 years, maybe within a factor of 3. But there is one important exception: if we have the ability to prevent or shape a “lock-in” scenario within this timeframe. By lock-in I mean anything which humanity can never escape from. Extinction risks are an obvious example, others are permanent civilisational collapse.

I am aware that Bostrom’s canonical definition of existential risks includes both of these lock-in scenarios, but it also includes scenarios which I consider to be irrelevant (failing to reach a transhumanist future), which is why I am not using the term in this section.

Thinking we cannot reliably impact the world for more than several decades, I do not find working on cause areas like ‘improving institutional decision-making’ compelling except for their ability to shape or prevent a lock-in in that timeframe..

I am also only interested in lock-in scenarios which would be as bad or worse than the current world, or maybe not much better. I am not interested in preventing a future in which humans just watch Netflix all day - it would be pretty disappointing, but at least better than a world in which people routinely starve to death.

At the moment, I do not know enough about the probabilities of a range of bad lock-in scenarios to judge whether focusing on them is warranted under my worldview. If this turns out to be the case on further investigation, I could imagine describing my worldview as longtermist when pushed, but I expect I would still feel a cultural disconnect with other longtermists.

If there are no options to avoid or shape bad lock-in scenarios within the next few decades, I expect improving the world with “traditional neartermist” approaches is best. My views here are very similar to Alexander Berger’s which he laid out in this 80,000 Hours podcast .

What would convince me otherwise:

If there have been any intentional impacts for more than a few hundred years out, I would be keen to know about them. I am familiar with Carl’s blogposts on the topic.

I expect to spend some time investigating this crux soon: if there are bad lock-in scenarios on the horizon which we can avoid or shape, that would likely change my feelings on longtermism.

Given that this is an important crux one might well consider it premature for me to draw conclusions about my worldview already. But my other views seem sufficiently different to most of the longtermist views I hear that they were hopefully worth lying out regardless.

If anyone has any resources they want to point me to which might change my mind, I am keen to hear about them.

Thanks to AGB and Linch Zhang for providing comments on a draft of this post.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This Can’t Go On #

Audio version available at Cold Takes (or search Stitcher, Spotify, Google Podcasts, etc. for “Cold Takes Audio”)

This piece starts to make the case that we live in a remarkable century, not just a remarkable era. Previous pieces in the series talked about the strange future that could be ahead of us eventually (maybe 100 years, maybe 100,000).

Summary of this piece:

- We’re used to the world economy growing a few percent per year. This has been the case for many generations.

- However, this is a very unusual situation. Zooming out to all of history, we see that growth has been accelerating; that it’s near its historical high point; and that it’s faster than it can be for all that much longer (there aren’t enough atoms in the galaxy to sustain this rate of growth for even another 10,000 years).

- The world can’t just keep growing at this rate indefinitely. We should be ready for other possibilities: stagnation (growth slows or ends), explosion (growth accelerates even more, before hitting its limits), and collapse (some disaster levels the economy).

The times we live in are unusual and unstable. We shouldn’t be surprised if something wacky happens, like an explosion in economic and scientific progress, leading to technological maturity . In fact, such an explosion would arguably be right on trend.

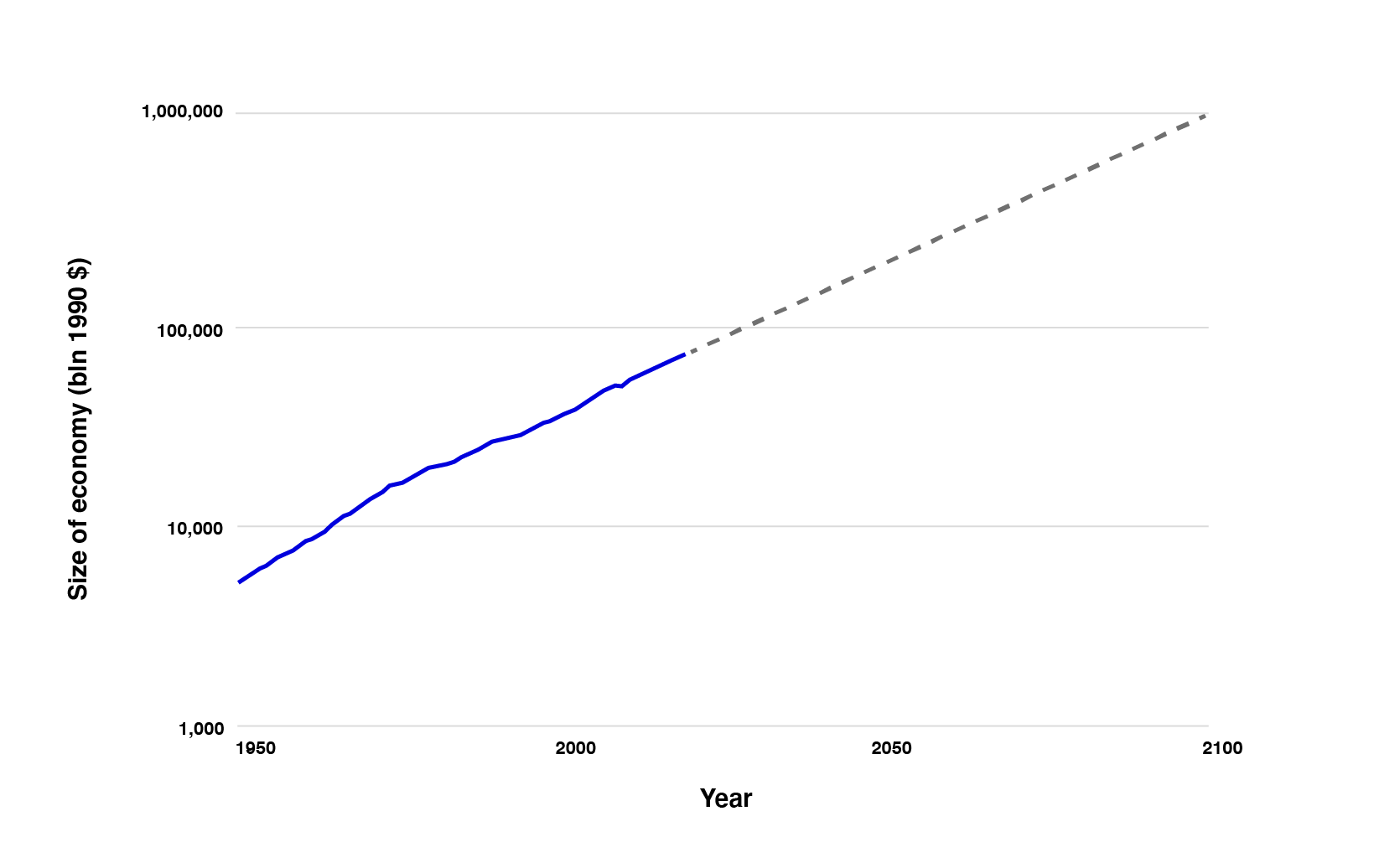

For as long as any of us can remember, the world economy has grown64 a few percent per year, on average. Some years see more or less growth than other years, but growth is pretty steady overall.65 I’ll call this the Business As Usual world.

In Business As Usual, the world is constantly changing, and the change is noticeable, but it’s not overwhelming or impossible to keep up with. There is a constant stream of new opportunities and new challenges, but if you want to take a few extra years to adapt to them while you mostly do things the way you were doing them before, you can usually (personally) get away with that. In terms of day-to-day life, 2019 was pretty similar to 2018, noticeably but not hugely different from 2010, and hugely but not crazily different from 1980.66

If this sounds right to you, and you’re used to it, and you picture the future being like this as well, then you live in the Business As Usual headspace. When you think about the past and the future, you’re probably thinking about something kind of like this:

Business As Usual

Business As Usual

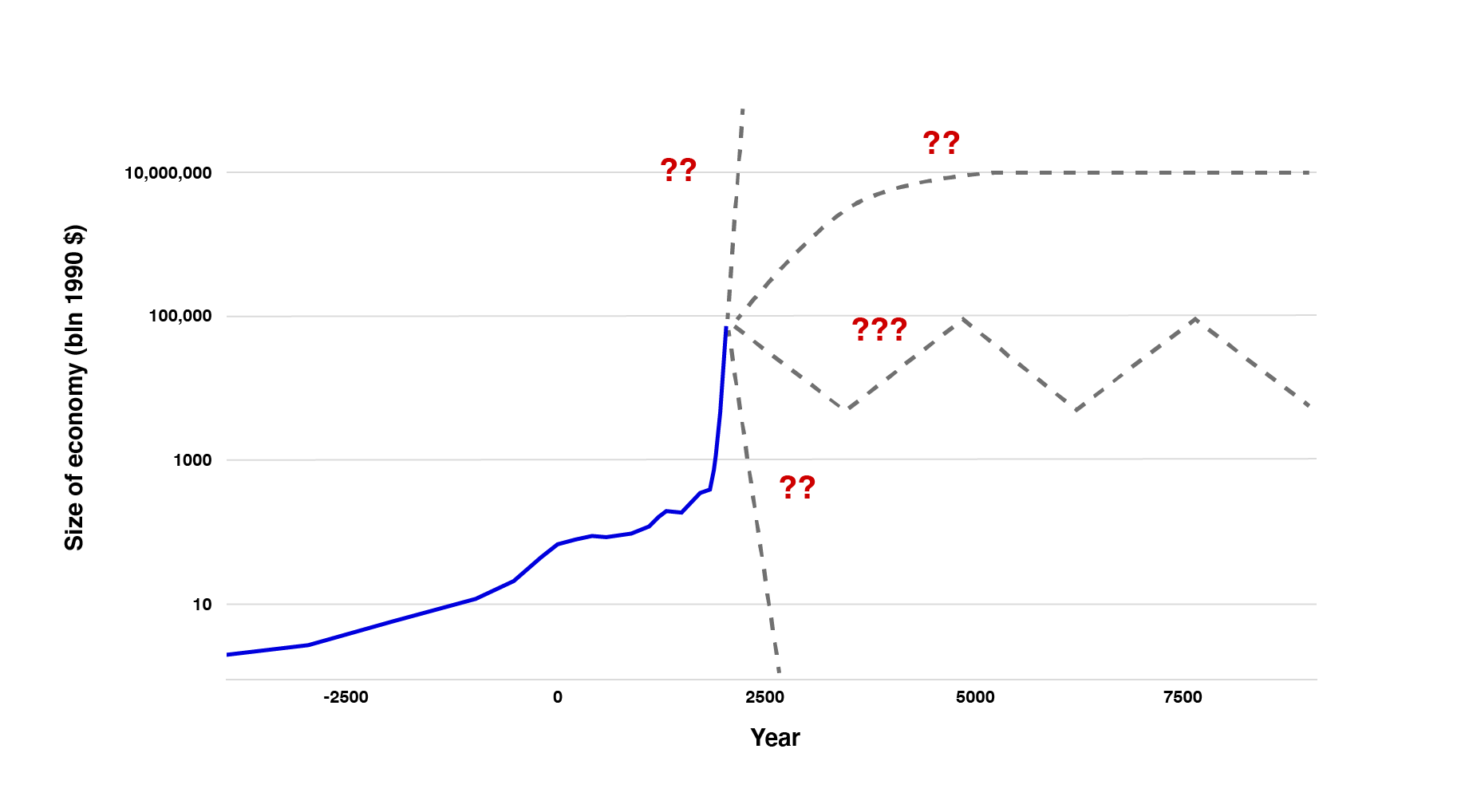

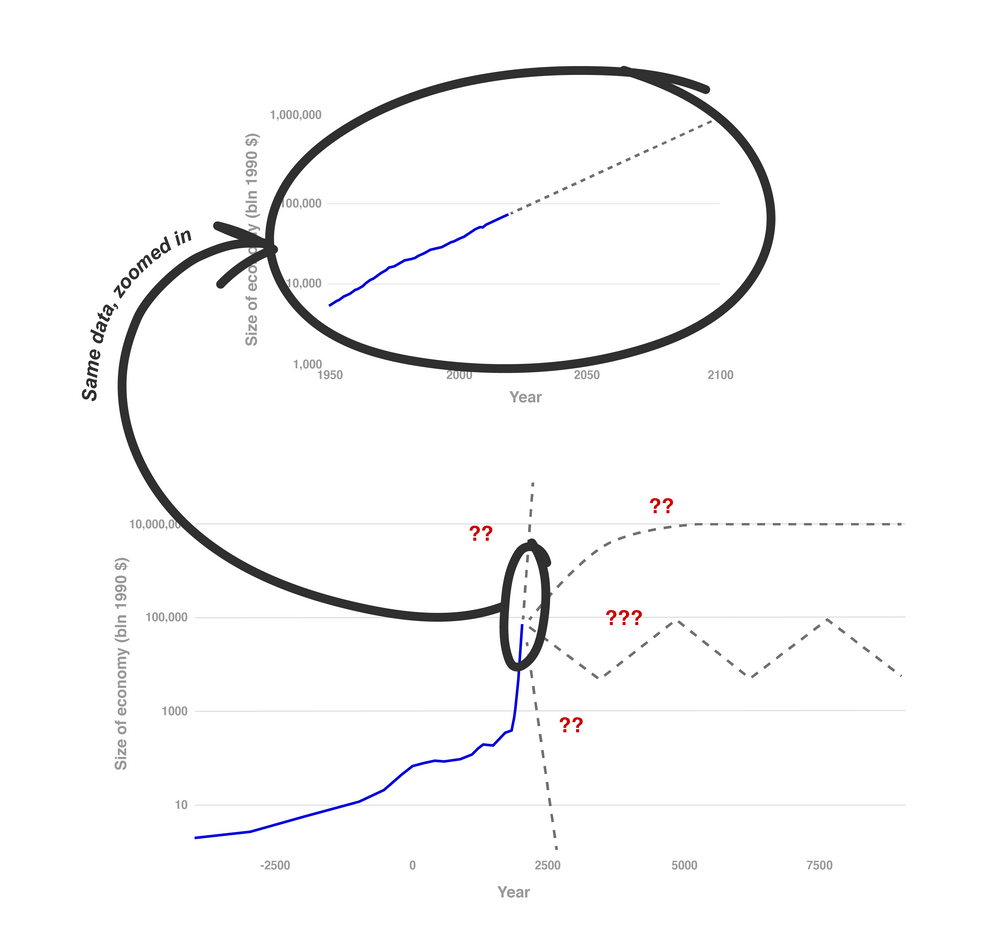

I live in a different headspace, one with a more turbulent past and a more uncertain future. I’ll call it the This Can’t Go On headspace. Here’s my version of the chart:

This Can’t Go On67

This Can’t Go On67

Which chart is the right one? Well, they’re using exactly the same historical data - it’s just that the Business As Usual chart starts in 1950, whereas This Can’t Go On starts all the way back in 5000 BC. “This Can’t Go On” is the whole story; “Business As Usual” is a tiny slice of it.

Growing at a few percent a year is what we’re all used to. But in full historical context, growing at a few percent a year is crazy. (It’s the part where the blue line goes near-vertical.)

This growth has gone on for longer than any of us can remember, but that isn’t very long in the scheme of things - just a couple hundred years, out of thousands of years of human civilization. It’s a huge acceleration, and it can’t go on all that much longer. (I’ll flesh out “it can’t go on all that much longer” below .)

The first chart suggests regularity and predictability. The second suggests volatility and dramatically different possible futures.

One possible future is stagnation: we’ll reach the economy’s “maximum size” and growth will essentially stop. We’ll all be concerned with how to divide up the resources we have, and the days of a growing pie and a dynamic economy will be over forever.

Another is explosion: growth will accelerate further, to the point where the world economy is doubling every year, or week, or hour. A Duplicator -like technology (such as digital people or, as I’ll discuss in future pieces, advanced AI) could drive growth like this. If this happens, everything will be changing far faster than humans can process it.

Another is collapse: a global catastrophe will bring civilization to its knees, or wipe out humanity entirely, and we’ll never reach today’s level of growth again.

Or maybe something else will happen.

Why can’t this go on? #

A good starting point would be this analysis from Overcoming Bias , which I’ll give my own version of here:

- Let’s say the world economy is currently getting 2% bigger each year.68 This implies that the economy would be doubling in size about every 35 years.69

- If this holds up, then 8200 years from now, the economy would be about 3*1070 times its current size.

- There are likely fewer than 1070 atoms in our galaxy,70 which we would not be able to travel beyond within the 8200-year time frame.71

- So if the economy were 3*1070 times as big as today’s, and could only make use of 1070 (or fewer) atoms, we’d need to be sustaining multiple economies as big as today’s entire world economy per atom.

8200 years might sound like a while, but it’s far less time than humans have been around. In fact, it’s less time than human (agriculture-based) civilization has been around.

Is it imaginable that we could develop the technology to support multiple equivalents of today’s entire civilization, per atom available? Sure - but this would require a radical degree of transformation of our lives and societies, far beyond how much change we’ve seen over the course of human history to date. And I wouldn’t exactly bet that this is how things are going to go over the next several thousand years.

It seems much more likely that we will “run out” of new scientific insights, technological innovations, and resources, and the regime of “getting richer by a few percent a year” will come to an end. After all, this regime is only a couple hundred years old.

( This post does a similar analysis looking at energy rather than economics. It projects that the limits come even sooner. It assumes 2.3% annual growth in energy consumption (less than the historical rate for the USA since the 1600s), and estimates this would use up as much energy as is produced by all the stars in our galaxy within 2500 years.72)

Explosion and collapse #

So one possible future is stagnation: growth gradually slows over time, and we eventually end up in a no-growth economy. But I don’t think that’s the most likely future.

The chart above doesn’t show growth slowing down - it shows it accelerating dramatically. What would we expect if we simply projected that same acceleration forward?

Modeling the Human Trajectory (by Open Philanthropy’s David Roodman) tries to answer exactly this question, by “fitting a curve” to the pattern of past economic growth.73 Its extrapolation implies infinite growth this century. Infinite growth is a mathematical abstraction, but you could read it as meaning: “We’ll see the fastest growth possible before we hit the limits.”

In The Duplicator , I summarize a broader discussion of this possibility. The upshot is that a growth explosion could be possible, if we had the technology to “copy” human minds - or something else that fulfills the same effective purpose, such as digital people or advanced enough AI.

In a growth explosion, the annual growth rate could hit 100% (the world economy doubling in size every year) - which could go on for at most ~250 years before we hit the kinds of limits discussed above.74 Or we could see even faster growth - we might see the world economy double in size every month (which we could sustain for at most 20 years before hitting the limits75), or faster.

That would be a wild ride: blindingly fast growth, perhaps driven by AIs producing output beyond what we humans could meaningfully track, quickly approaching the limits of what’s possible, at which point growth would have to slow.

In addition to stagnation or explosive growth, there’s a third possibility: collapse. A global catastrophe could cut civilization down to a state where it never regains today’s level of growth. Human extinction would be an extreme version of such a collapse. This future isn’t suggested by the charts, but we know it’s possible.

As Toby Ord’s The Precipice argues, asteroids and other “natural” risks don’t seem likely to bring this about, but there are a few risks that seem serious and very hard to quantify: climate change, nuclear war (particularly nuclear winter), pandemics (particularly if advances in biology lead to nasty bioweapons), and risks from advanced AI.

With these three possibilities in mind (stagnation, explosion and collapse):

- We live in one of the (two) fastest-growth centuries in all of history so far. (The 20th and 21st.)

- It seems likely that this will at least be one of the ~80 fastest-growing centuries of all time.76

- If the right technology comes along and drives explosive growth, it could be the #1 fastest-growing century of all time - by a lot.

- If things go badly enough, it could be our last century.

So it seems like this is a quite remarkable century, with some chance of being the most remarkable. This is all based on pretty basic observations, not detailed reasoning about AI (which I will get to in future pieces).

Scientific and technological advancement #

It’s hard to make a simple chart of how fast science and technology are advancing, the same way we can make a chart for economic growth. But I think that if we could, it would present a broadly similar picture as the economic growth chart.

A fun book I recommend is Asimov’s Chronology of Science and Discovery . It goes through the most important inventions and discoveries in human history, in chronological order. The first few entries include “stone tools,” “fire,” “religion” and “art”; the final pages include “Halley’s comet” and “warm superconductivity.”

An interesting fact about this book is that 553 out of its 654 pages take place after the year 1500 - even though it starts in the year 4 million BC. I predict other books of this type will show a similar pattern,77 and I believe there were, in fact, more scientific and technological advances in the last ~500 years than the previous several million.78

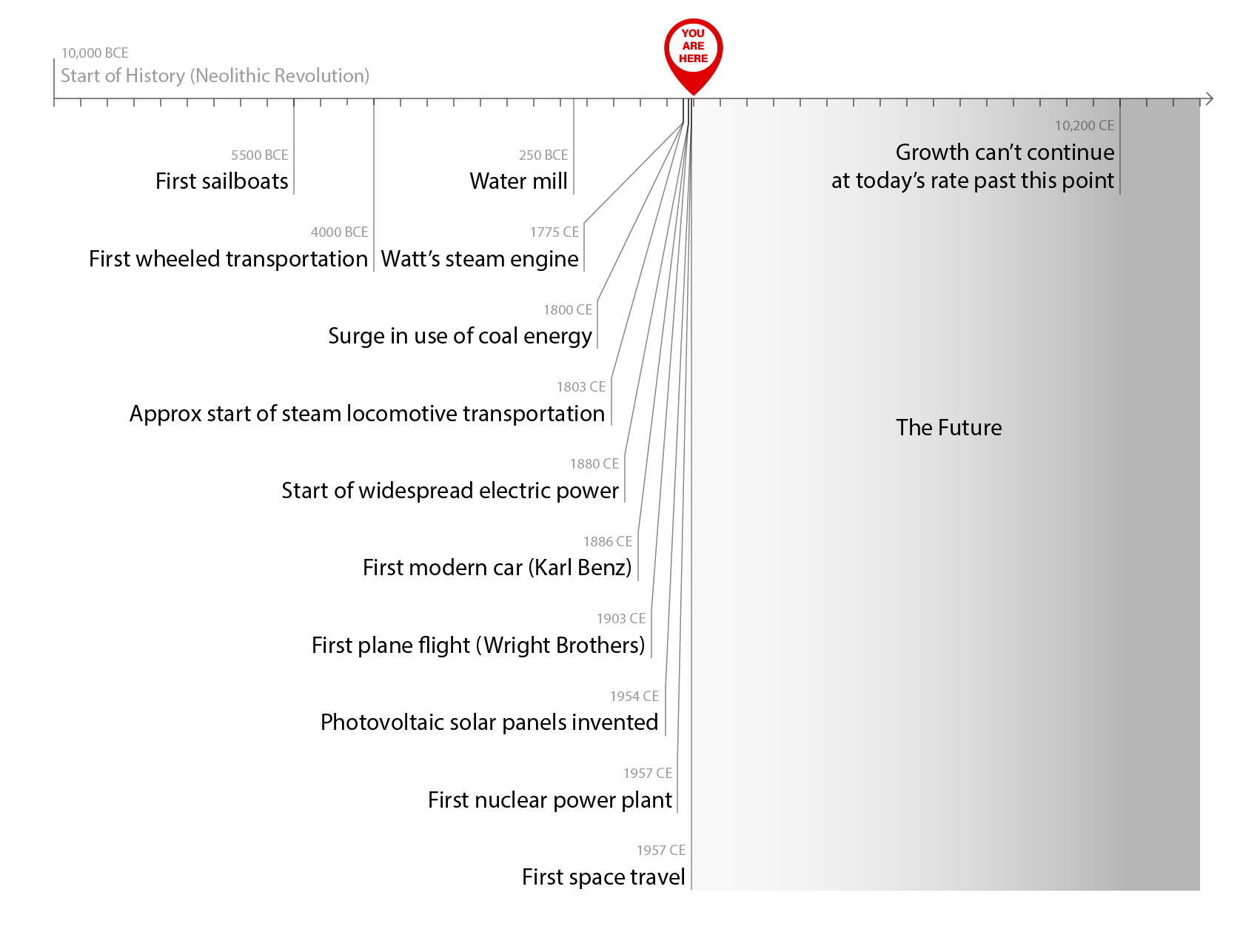

In a

previous piece

, I argued that the most significant events in history seem to be clustered around the time we live in, illustrated with

this timeline

. That was looking at billions-of-years time frames. If we zoom in to thousands of years, though, we see something similar: the biggest scientific and technological advances are clustered very close in time to now. To illustrate this, here’s a timeline focused on transportation and energy (I think I could’ve picked just about any category and gotten a similar picture).

In a

previous piece

, I argued that the most significant events in history seem to be clustered around the time we live in, illustrated with

this timeline

. That was looking at billions-of-years time frames. If we zoom in to thousands of years, though, we see something similar: the biggest scientific and technological advances are clustered very close in time to now. To illustrate this, here’s a timeline focused on transportation and energy (I think I could’ve picked just about any category and gotten a similar picture).

So as with economic growth, the rate of scientific and technological advancement is extremely fast compared to most of history. As with economic growth, presumably there are limits at some point to how advanced technology can become. And as with economic growth, from here scientific and technological advancement could:

- Stagnate , as some are concerned is happening .

- Explode , if some technology were developed that dramatically increased the number of “minds” (people, or digital people , or advanced AIs) pushing forward scientific and technological development.79

- Collapse due to some global catastrophe.

Neglected possibilities #

I think there should be some people in the world who inhabit the Business As Usual headspace, thinking about how to make the world better if we basically assume a stable, regular background rate of economic growth for the foreseeable future.

And some people should inhabit the This Can’t Go On headspace, thinking about the ramifications of stagnation, explosion or collapse - and whether our actions could change which of those happens.

But today, it seems like things are far out of balance, with almost all news and analysis living in the Business As Usual headspace.

One metaphor for my headspace is that it feels as though the world is a set of people on a plane blasting down the runway:

We’re going much faster than normal, and there isn’t enough runway to do this much longer … and we’re accelerating.

And every time I read commentary on what’s going on in the world, people are discussing how to arrange your seatbelt as comfortably as possible given that wearing one is part of life, or saying how the best moments in life are sitting with your family and watching the white lines whooshing by, or arguing about whose fault it is that there’s a background roar making it hard to hear each other.

If I were in this situation and I didn’t know what was next (liftoff), I wouldn’t necessarily get it right, but I hope I’d at least be thinking: “This situation seems kind of crazy, and unusual, and temporary. We’re either going to speed up even more, or come to a stop, or something else weird is going to happen.”

Thanks to María Gutiérrez Rojas for the graphics in this piece, and Ludwig Schubert for an earlier timeline graphic that this piece’s timeline graphic is based on.

To check my 2% guess, I downloaded this US data and looked at the annualized growth rate between 2000-2020, 2010-2020, and 2015-2020 (all using July since July was the latest 2020 point). These were 2.5%, 2.2% and 2.05% respectively.

Superforecasting in a nutshell #

This is a linkpost for http://lukemuehlhauser.com/superforecasting-in-a-nutshell/

Let’s say you want to know how likely it is that an innovative new product will succeed, or that China will invade Taiwan in the next decade, or that a global pandemic will sweep the world — basically any question for which you can’t just use “ predictive analytics ,” because you don’t have a giant dataset you can plug into some statistical models like (say) Amazon can when predicting when your package will arrive.

Is it possible to produce reliable, accurate forecasts for such questions?

Somewhat amazingly, the answer appears to be “yes, if you do it right.”

Prediction markets are one promising method for doing this, but they’re mostly illegal in the US, and various implementation problems hinder their accuracy for now. Fortunately, there is also the “ superforecasting ” method, which is completely legal and very effective.

How does it work? The basic idea is very simple. The steps are:

-

First, bother to measure forecasting accuracy at all. Some industries care a lot about their forecasting accuracy and therefore measure it, for example hedge funds. But most forecasting-heavy industries do not even bother to measure their forecasting accuracy,80 for example the US intelligence community or philanthropy.81

-

Second, identify the people who are consistently more accurate than everyone else — say, those in the top 0.1% for accuracy, for multiple years in a row. These are your “superforecasters.”

-

Finally, pose your forecasting questions to the superforecasters, and use an aggregate of their predictions.

Technically, the usual method is a bit more complicated than that,82 but these three simple steps are the core of the superforecasting method.

So, how well does this work?

A few years ago, the US intelligence community tested this method in a massive, rigorous forecasting tournament that included multiple randomized controlled trials and produced over a million forecasts on >500 geopolitical forecasting questions such as “Will there be a violent incident in the South China Sea in 2013 that kills at least one person?” This study found that:

-

This method produced forecasts that were very well-calibrated, in the sense that forecasts made with 20% confidence came true 20% of the time, forecasts made with 80% confidence came true 80% of the time, and so on. The method is not a crystal ball; it can’t tell you for sure whether China will invade Taiwan in the next decade, but if it tells you there’s a 10% chance, then you can be pretty confident the odds really are pretty close to 10%, and decide what policy is appropriate given that level of risk.83

-

This method produced forecasts that were far more accurate than those of a typical forecaster or other approaches that were tried, and ~30% more accurate than intelligence community analysts who (unlike the superforecasters84) had access to expensively-collected classified information and years of training in the geopolitical issues they were making forecasts about.85 Those are pretty amazing results! And from an unusually careful and rigorous study, no less!86

So you might think the US intelligence community has eagerly adopted the superforecasting method, especially since the study was funded by the intelligence community, specifically for the purpose of discovering ways to improve the accuracy of US intelligence estimates used by policymakers to make tough decisions. Unfortunately, in my experience, very few people in the US intelligence and national security communities have even heard of these results, or even the term “superforecasting.”87

A large organization such as the CIA or the Department of Defense has enough people, and makes enough forecasts, that it could implement all steps of the superforecasting method itself, if it wanted to. Smaller organizations, fortunately, can just contract already-verified superforecasters to make well-calibrated forecasts about the questions of greatest importance to their decision-making. In particular:

-

The superforecasters who out-predicted intelligence community analysts in the forecasting tournament described above are available to be contracted through Good Judgment Inc.

-

Another company, Hypermind, offers aggregated forecasts from “champion forecasters,” i.e. the most accurate forecasters across thousands of forecasting questions for corporate clients going back (in some cases) almost two decades.88

-

Several other projects, for example Metaculus , are also beginning to identify forecasters with unusually high accuracy across hundreds of questions.